The UK government’s Energy White Paper: Powering our net zero future, published on 14 December 2020, was long promised. Was it worth the wait? If you were expecting the sort of White Paper that sets a new strategic direction, or that describes in a lot of detail how specific policies previously only outlined will be implemented, you will be disappointed. Instead, we have a stock-take of current energy policies and a detailed agenda for what promises to be several years of significant new policy development. It is none the worse for that: the first deliverables highlighted in the White Paper appeared within days of its publication and already show progress in several areas. And what is envisaged will create new markets and may significantly reform existing ones.

The White Paper’s title echoes the 2011 Energy White Paper Planning our electric future: a white paper for secure, affordable and low-carbon energy, which set out the policies of the coalition government’s Electricity Market Reform (EMR) project. A comparison of the two documents shows both how far we have come and how much remains to be done. Huge progress has been made in decarbonising UK electricity generation, but EMR left plenty of unfinished business even there. It did not, for example, try to reform electricity markets or their institutions and governance to reflect the sector’s increasingly distributed and digitalised character or the substantial displacement of fossil fuels by less polluting technologies. Moreover, the challenge now identified by the government is both to achieve deeper decarbonisation of electricity and to go beyond electricity. EMR was able to achieve progress by incentivising actions by a relatively small number of electricity industry players. Government now wants to move forward in other areas: energy efficiency, heat, transport and industrial decarbonisation. Here, millions of consumers and businesses not focused on energy need to invest significant sums, and change their behaviour, if the UK is to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Many of them will be “encouraged” to replace fossil fuels with clean electricity, leading to a doubling of electricity demand, met by cleaner energy capacity and modernised energy markets.

The White Paper is explicitly a kind of companion piece to the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution (TPP), published less than a month ago, which summarised some of the more eye-catching aspects of the government’s energy and climate policies, and which we have written about here and here. It shares with the TPP an emphasis on how the policies it discusses, as well as contributing to net zero goals in the UK, will also promote a “green recovery” from the COVID-19 pandemic; help to “level up” economically disadvantaged parts of the UK; and demonstrate the UK’s climate leadership role (and so export opportunities) in the (extended) year of its UNFCCC CoP presidency.

We review the White Paper (and some of the follow-up to it that has already emerged) below, using the headings of its six numbered chapters. A theme across the whole White Paper is the critical need for significant change – to the behaviours of business and the public and so to the markets, policies and law needed to secure that change.

Chapter 1 – Consumers

Key messages

The White Paper aims to provide a vision of what “the transition to clean energy by 2050…will mean for [domestic or business] consumers of energy”. The policies it previews aim to ensure consumers get the benefit of new technologies (e.g. smart metering enabling time-of-use tariffs, smart charging and vehicle-to-grid), whilst addressing concerns about the competitiveness of retail energy markets and energy poverty. There is also an awareness that, by itself, technological progress and decarbonisation can cause problems, as well as solving them. For example, how should regulation address the potential impact of consumers taking advantage of the ability to generate their own renewable electricity: who pays for the grid if predominantly affluent households become more or less independent of the public energy networks in this way? More generally, there is the challenge of maintaining consumer protection as technologies and services evolve.

Chapter 1 of the White Paper is dedicated to the viewpoint of the end-users of energy, but it is reflected throughout the document. As it says: “The way that…costs are passed through to bills can incentivise or disincentivise certain types of consumer behaviour”. The challenge is that, so far, millions of domestic electricity and gas customers ignore the existing, basic price signals in the market. Over 50% are on default tariffs, even though almost all know they can switch, and many more or less consciously pay a “loyalty penalty” for not doing so. Will those of us who are still only passive participants in the market be prompted to change our attitude by the prospect of being able to make further savings or gains by running washing machines and charging EVs when wholesale power prices are low, or of charging an extra household battery when they are negative? The answer may be “yes” if a significantly greater share of the home wallet is spent on electricity (because the home EV charging station will replace the petrol station and an electric heating system will replace gas) but the White Paper also hints that regulation may compel as well as incentivise.

Policy pipeline

In “early” or “spring” 2021, the White Paper promises the following.

- Conclusion of the HM Treasury review on funding the transition to net zero (which began in 2019, at the prompting of the Committee on Climate Change (CCC)). An interim report from the review emerged within a few days of the White Paper’s publication. It contains some useful economic information and analysis, but its conclusions so far are anodyne (samples: “The costs of the transition to net zero are uncertain and depend on policy choices”; “Households are exposed to the transition through their consumption, labour market participation and asset holdings”). Unless we have missed something, there is no hint here of, for example, a decisive shift in carbon taxation, or a move away from subsidising clean energy on the proceeds of consumer levies that are arguably inherently regressive. However, this is essentially an exercise in setting the background to policy, rather than policy itself, and perhaps we should not rush to judgment until the final report emerges.

- “A call for evidence [by April 2021] to begin a strategic dialogue between government, consumers and industry on affordability and fairness” including the distribution of net zero costs (demographically and, for example, as between gas and electricity consumers).

- A final decision from Ofgem (spring 2021) on when and how to implement the proposals for market-wide half hourly settlement in the electricity market, which have been gestating for years.

- Consultations on opt-in switching (to be implemented by 2024) and on how auto-renewal and roll-over tariff arrangements can be reformed (March 2021).

- A consultation on reforms to ensure consumers have transparent information about things like the carbon content of the energy supplied to them.

- A consultation on retail market reform, e.g. about regulating intermediaries such as energy brokers and price comparison websites (spring 2021).

We are also promised action in other areas – either in 2021 generally, or without an explicit indication of timing, but in a context that suggests that next steps will or may be taken at some point next year.

- A consultation on the expansion and terms of the Energy Company Obligation and Warm Home Discount schemes (ECO and WHD) that respectively aim to improve the energy efficiency of the homes, and provide a cash discount on the bills, of poorer customers. ECO and WHD obligations fall on energy suppliers in the first instance, but only if they have more than 250,000 customers. This helps small suppliers, but creates a number of market distortions: how can these best be removed?

- It is three years since Ofgem’s then CEO asked “Do the ‘supplier hub’ market rules need reform?”. The White Paper is guarded about the need for “market framework changes…to facilitate the development and uptake of innovative tariffs and products that work for consumers and contribute to net zero”. There will be engagement with industry and consumer groups throughout 2021 before a formal consultation, as the government assesses “whether incremental changes…are sufficient or whether more fundamental changes are required”.

- Data is key to empowering consumers and developing innovative energy business models that can improve their experience, offer them more choice and benefit them financially. In the standard phrase used where primary legislation may be required to introduce new policies, the government is planning to “legislate when Parliamentary time allows” on smart appliances, to address issues of interoperability, data privacy and cyber security. Such provisions could presumably be part of a Bill focused on either “digital” or “energy” issues. No doubt 2021 will also see more outputs from the Modernising Energy Data programme.

Chapter 2 – Power

Key messages

Power (generation) is the area where most decarbonisation has been achieved already, and where the government’s most notable goals and commitments (like 40GW of offshore wind, including 1GW floating, by 2030, and £160 million of investment in manufacturing facilities) have already been extensively aired in the TPP and elsewhere. The White Paper paints the big picture clearly enough: electricity could provide more than half of final energy demand in 2050, up from 17% in 2019. This would require a four-fold increase in clean electricity generation. However, ministers will not determine the precise generation mix and the commitment to market mechanisms remains.

Note – “clean”, and not just green. For more flexible low carbon generation, the government is keen to develop gas-fired power with CCUS (or hydrogen) as part of its industrial cluster SuperPlaces; for low carbon baseload, nuclear remains a major focus of immediate investment and technology development. A few hours before publishing the White Paper, it confirmed its decision to begin negotiations with EDF (and its Chinese state-owned partner) about the proposed Sizewell C nuclear plant. There are significant funding programmes for small modular reactors (SMRs) and advanced modular reactors (AMR), and support for nuclear fusion. These are expected to bear fruit in the 2030s and beyond. In the meantime, there is a target to “bring at least one large-scale nuclear project to the point of FID by the end of this Parliament, subject to clear value for money and all relevant approvals”. The White Paper announces a degree of progress towards a new regulatory and funding framework for public funding and regulation of new-build nuclear (see below), including potential capital support for construction, though it leaves options previously canvassed open.

Though there are no new, immediate funding announcements for them, there is encouragement for investors in battery and long-term storage, demand response technologies and interconnectors, which the government says it expects to form key parts of the (predominantly wind and solar) generation mix, alongside the other clean technologies discussed elsewhere in this note. Less so for wave and tidal technologies, which are to be studied further as evidence about them emerges.

For fossil-fuel plant operators, the day on which the White Paper was published also brought clarity in the form of an announcement confirming that the UK would replace the portion of its carbon pricing regime that has hitherto been provided by the “cap and trade” EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) with a UK ETS, rather than the alternative mechanism of a Carbon Emissions Tax (see Chapter 5 below).

Policy pipeline

On the agenda for 2021 are:

- opening to SMRs the nuclear Generic Design Assessment process for assessing the safety, security and environmental implications of new nuclear reactor designs;

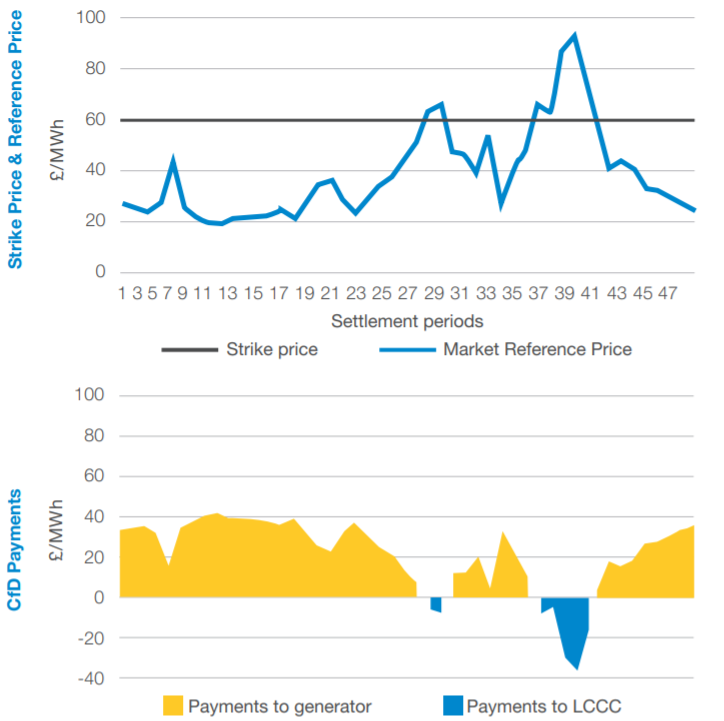

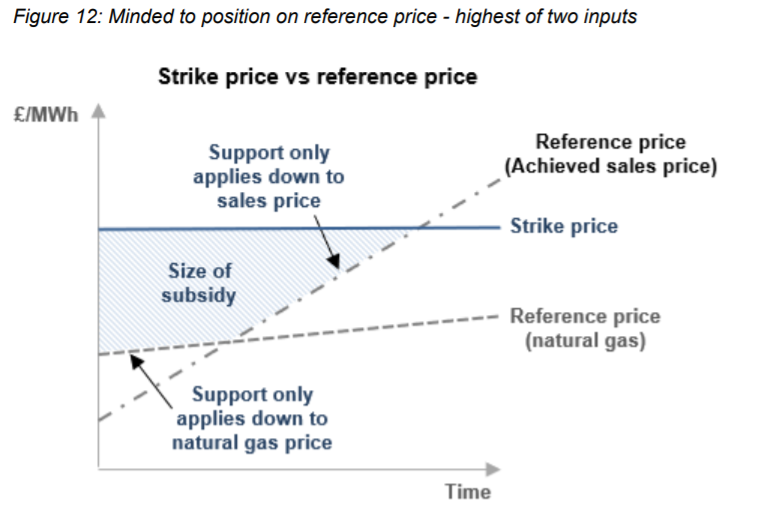

- more development of the CfD support framework for renewables. A number of changes to the regime have already been announced or are being consulted on in the context of the fourth CfD Allocation Round (AR4), which is due in “late 2021”, including requiring adherence to developers’ supply chain plans, aimed to deliver 60% UK content in offshore wind by 2030. At the same time, the White Paper confirms this as the primary instrument for public funding of new and existing renewable generation technologies, until these can operate without subsidy, with auctions every two years with increasing scale confirmed. Government is looking beyond AR4 and considering how to maintain growth in renewable deployment while ensuring overall system costs for electricity consumers are minimised and innovative technologies and business models are supported. To this end, it has published Enabling a high renewable, net zero electricity system: call for evidence. The 22 questions in this document cover a wide range of topics: everything from the impact on cost of capital of introducing greater exposure to the market price for power, to the accommodation of hybrid and international projects in the CfD regime, to the interface of the CfD regime and Ofgem’s Access and Forward-Looking Charges Review and the Balancing Services Charges Task Force. This is an extremely important publication that all stakeholders in the GB renewables sector would do well to engage with seriously (the call for evidence runs until 22 February 2021). It seems highly likely that further consultations will follow during 2021 or early in 2022;

- a call for evidence on the role of biomass in net zero power: in particular, by 2022, it will be established what role biomass with CCS (BECCS) can play in reducing carbon emissions and how it could be deployed (as part of a wider biomass strategy taking account, as biomass policy always must, of how sustainable the use of biomass for energy purposes is). If nothing else, this may be an important part of the evaluation of any bid for CCUS funding that includes the large biomass units at Drax, whose current revenue support expires before 2030. A wider call for evidence on greenhouse gas removal technologies (which includes BECCS, but also Direct Air CCS (DACCS) and others) is currently open;

- a review of the national (planning) policy statements (NPSs) that provide the policy background for development consents for major new energy infrastructure in England and Wales, with fresh NPSs to be designated by the end of the year. Depending on how far work on this has already progressed, this is not an unambitious target, given the requirements for statutory consultation, appraisal of sustainability and Parliamentary approval before designation. Since the NPSs were originally designated, new technologies, not dealt with in the current versions, have (or will soon have) crossed the 50MW threshold from which they apply, including solar, various forms of storage and floating offshore wind;

- large-scale gas-fired power – an area where there is likely to be lively debate on the NPSs. In the last decade, much of this has been consented, but almost none built. The prospect of support being available for plants with CCUS raises obvious questions about the existing NPS policies in this area. Should revised NPSs seek to restrict new consents for gas-fired projects to sites with credible links to proposed CCUS clusters? The typical instinct of UK energy infrastructure policy-makers is never to prescribe more than they feel they absolutely have to. Meanwhile, the White Paper promises a consultation in early 2021 on ways to remove the requirement for proposed new combustion plant with a capacity of 300MW or more to be consented only if it is considered technically and economically feasible to retrofit CCS to it within its operational life. Given the range of projects that have been deemed to satisfy this criterion, it may be doubted whether it has in practice been that onerous, but it is, of course, true that there are likely to be more ways for a CCGT plant to become CO2 emission-free in the future than retrofitting CCS – for example, by converting to run on hydrogen (which need not necessarily be produced in a CCUS cluster: it could, for example, be produced by the electrolysis of water using electricity generated from renewable, or even nuclear, sources);

- CHP – shortly before the White Paper was published, the government released a summary of responses to Combined Heat and Power (CHP): the route to 2050 – call for evidence. A more detailed consultation on CHP issues is to follow in 2021;

- assessment of the synergies between offshore wind and hydrogen production; and

- establishment of a “Ministerial Delivery Group” to ensure joined up government.

Supporting analysis/other documents published with the White Paper

The White Paper was published alongside a number of other documents, many of which relate to aspects of power generation policy.

- In July 2019, the government consulted on a Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model for nuclear. It was thought that a RAB model with some of the characteristics of the funding and support package for the Thames Tideway Tunnel would reduce the cost of capital for future new nuclear projects, making them cheaper than the funding and support package for Hinkley Point C. What we have now is not an elaboration of the elements of a proposed nuclear RAB regime, but a summary of the responses to the July 2019 consultation with some very brief conclusions, such as that “if any model is to attract private financing”, it will require a variable £/MWh price, “allowing for the revenue stream to be adjusted by the Regulator as circumstances change”; allowed revenue during construction “to reduce the scale and capital cost of financing” and reduce total costs; and “some level of risk sharing between investor and consumers/taxpayers”. It sounds as if government will develop policy in the course of its negotiations with EDF and the promoters of other large nuclear projects still going forward.

- The White Paper states the familiar adage: “The electricity market should determine the best solutions for very low emissions and reliable supply, at a low cost to consumers”. Since “the electricity market” is largely the product of policy and regulatory choices, that comment only takes us so far. However, the government has been refining the modelling that is used to look at illustrative mixes of generation compatible with net zero. Some show two to three times as much nuclear as now, and half to a third as much gas-fired generation, but with CCUS. In all, 7,000 different mixes have been modelled, for two different levels of demand and flexibility and 27 different technology cost combinations, giving more than 700,000 unique scenarios. The accompanying Modelling 2050 – electricity system analysis paper concludes that there is no single optimal mix; that system costs are lowest when carbon intensity is 5-25gCO2/kWh; that there is some substitutability between hydrogen-fired generation and long-term storage on the one hand and nuclear and gas with CCUS on the other; and that more analysis is needed.

- In 2016, the government consulted on proposals to legislate for the phasing out of coal-fired generation in GB. These have yet to be implemented, but now it has issued a further consultation on Early phase-out of unabated coal generation in Great Britain – the idea now being to ban coal-fired generation from 1 October 2024, rather than 1 October 2025. In the meantime, more coal-fired plant has closed; the amount of capacity with obligations under the Capacity Market has fallen from 10.5GW in the 2017/18 delivery year to 1.3GW in the T-4 auction for delivery in 2023/24; and 2019 has set new records for the number of days that have passed without coal-fired power being exported onto the network. Realistically, with coal unable to compete for Capacity Market payments after 1 October 2024, it may be unlikely that the remaining units would stay operational after that date in any event, but it makes sense to tie up this loose end of policy and secure a potential additional decarbonisation advantage.

Post-White Paper update

- When the government responded to the July 2019 consultation on CCUS business models in August 2020, it did not provide a great deal of new detail on its evolving thinking. In our own analysis of the 2019 consultation prior to the August 2020 response, we identified 63 questions (many of them with several parts) that government needed to answer in order to move forward with its ambitions for (then) two and (now) four CCUS clusters in the next decade. The August 2020 documents left many of these questions unanswered. We have not yet carried out an exact tally, but it is clear that the update on CCUS business models published on 21 December 2020 has now answered many more of them.

- The policy on CCUS power, in particular, has advanced considerably. Accompanying the general update document, Chapter 4 of which focuses on power, are a “detailed explanation” and a 111-page “heads of terms” relating to the Dispatchable Power Agreement (DPA) that will channel consumer-funded support to CCUS power stations in the form of Availability Payments and Variable Payments. Together, the documents make it a lot clearer in what respects the DPA terms will follow the pattern of EMR CfDs, and what their provisions will look like where they depart from the CfD model. Most of the “detailed explanation” document is taken up with about 20 pages explaining how the payment mechanisms are expected to work (also making clear the points on which decisions have yet to be made). There are formulae, with several pages defining the terms used in them. This is real progress, though the devil will be in the detail.

- The material on CCUS power is complemented by Chapter 3 of the update, on the transport and storage (T&S) elements of CCUS, on whose effective functioning everything else in the CCUS value chain ultimately depends. T&S is also the subject of two annexes to the update, setting out “draft commercial principles” for, respectively, a T&S licence and a government support package for T&S. There is less detail here than in the power documents, but it is becoming clearer how the “high impact, low probability” risks associated with T&S will be addressed, even if “the ownership model of the T&SCo” remains under consideration.

- There is not space here to do justice to the 21 December 2020 CCUS publications. We will comment on them further elsewhere. If you have questions about them, please get in touch.

Chapter 3 – Energy system

Key messages

The energy system chapter of the White Paper is about the physical (gas and electricity) infrastructures that connect energy supply and demand, and about the regulatory frameworks that govern the sector. Three quotes will give a flavour: “The prize is an energy system which is not only cleaner but also smarter”; the plan to “drive competition deep[er] into the operation of our energy markets”; and “Separate networks for electricity, gas for heating and petrol or diesel for cars and vans…will increasingly merge into one system, as electricity becomes the common energy currency”. As the chapter points out, further physical and regulatory adaptation will be needed for hydrogen and CCUS.

The subject matter of this chapter is extremely important but it can sometimes seem a little disparate and the lines of future policy are not always easy to discern from it.

On the gas side, there is talk of reviewing “the overarching regulatory framework set out in the Gas Act 1995”, removing distortions in the existing regulatory structure and allowing competition with lower carbon options while maintaining security of supply. A little later, we find:

“We need the operation of national and local energy markets to be managed impartially, without conflict of interest, ensuring they are fully open to competition. We need a robust process for setting and enforcing system rules, an approach which ensures that the rules promote competition and innovation, not act as a barrier to change. There is also a need for a greater co-ordination to drive collaboration between different parts of the energy system which are currently too siloed.

We need to consider, at both the transmission and distribution level, whether the roles which discharge these functions are undertaken by government, Ofgem, industry parties such as the system operator, or by an entirely new body. We will review the right long-term role and organisational structure for the ESO, in light of the reforms to the system operator instituted in April 2019. It is possible that there will need to be greater independence from the current ownership structure, should it be appropriate to confer additional roles on the system operator.

These new roles should help the system achieve our net zero ambitions and meet consumers’ needs. Without them, we risk having an energy system which makes less effective investment and operational decisions, resulting in excessive costs for consumers or a failure to reduce emissions in line with our net zero target.“

This sounds potentially quite radical. It echoes the statement in the National Infrastructure Strategy (NIS), published in November 2020: “The government will review the right long-term role and organisational structure for the Electricity System Operator”, and that “greater independence from the current ownership structure” may be required if “additional roles” are conferred on the System Operator. At a similarly fundamental level, the NIS also committed the government to producing “an overarching policy paper on economic regulation” in 2021 (see further below). It is clear that (possibly complete) separation of ownership and operation of the electricity system operator is on the agenda; the separation of the two functions, rather than a simpler nationalisation or ownership divestment requirement, presumably seeks to avoid the need to buy out existing system operator shareholders, who will retain the ownership function.

There is a commitment to “support the rollout of charging and associated grid infrastructure along the strategic road network, to support drivers to make the switch to EVs…”

Policy pipeline

A busy 2021 beckons for regulatory developments in relation to energy systems.

- The review of the gas legislation referred to above, with industry workshops throughout 2021.

- The government claims to have implemented two-thirds of the policies in the Smart Systems and Flexibility Plan that it published with Ofgem in 2017, and to be “on track to deliver it in full by 2022, removing barriers to energy storage, enabling smart homes and businesses and properly rewarding providers of flexibility services”. However, there is more to be done: “We are now ready to take the next step in driving flexibility deep into the energy system”, and a new Smart Systems Plan will be issued in spring 2021.

- Regulations are to be made under the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018 to mandate that private EV chargepoints must be capable of delivering smart charging.

- There is a promise to define electricity storage in legislation when Parliamentary time allows, although it is not clear whether or how it is proposed to change the regulatory treatment of storage (beyond existing initiatives) once it has been defined. In the shorter term, there is to be a major competition to accelerate commercialisation of first of a kind, longer duration energy storage. This will be focused on non-proven storage technologies.

- Another topic on which legislation is promised when Parliamentary time allows (and not for the first time) is enabling competitive tendering for, and building, ownership and operation of, the onshore electricity networks (transmission and distribution). Draft clauses on this were published and considered by a Parliamentary committee four years ago, and Ofgem did a considerable amount of work on what was referred to at the time as the CATO regime – aiming to bring some of the benefits of the offshore, OFTO regime to the onshore networks. Although hampered by the lack of Parliamentary follow-through on the required primary legislation, the project also seemed to lack early projects (other than connections to new nuclear power stations) on which to be showcased. Maybe it will be different this time, particularly if government is moving to separate (further) the system operation and network operation/ownership functions or arms of transmission and distribution groups.

- There is also a linkage with the perception that changes in technology mean that the answer to “network problems” today is not necessarily more traditional network infrastructure, whose value will be added to a network operator’s RAB. It may instead be infrastructure that is inherently more flexible, storage (which is treated as generation and therefore not generally to be owned by the networks) or a pure IT solution of some kind (i.e. not a physical asset at all). The possibility of “system operators” being independent commissioners of solutions from a range of providers/infrastructure owners begins to take shape. The White Paper notes that DNOs have already entered into contracts for 1.2GW of flexibility in 2020 without even having an explicitly recognised system operator function. It suggests that the network innovation funding awarded by Ofgem, which is currently part of the regulatory framework for licensed operators, could be opened up to a wider range of participants. The government wants to encourage more local solutions and open up as many services as possible to competition.

- Just as onshore networks seek to apply some of the learning of OFTOs, so the government and Ofgem are looking at ways that a more co-ordinated, and therefore perhaps onshore-like, approach could be taken to the development of offshore transmission, as the offshore wind sector is scheduled for enormous growth over the next 10 years. Some output from the current review process is to be expected in 2021, but a full picture will take time to emerge. Indeed, the White Paper seems to suggest that any more radical reshaping of an “offshore grid” may not happen until the 2030s. Although offshore wind projects in development are invited to express an interest in being “pathfinders”, it would perhaps inject too much uncertainty into forthcoming CfD auctions to implement fundamental change earlier.

- On 16 December 2020, National Grid ESO published a Phase 1 report from its offshore coordination project. This highlights the potential benefits of taking an “integrated approach” to the offshore network sooner (from 2025) rather than later (from 2030), including savings of £6 billion (or 18%), rather than £3 billion (or 8%), for consumers to 2050, and reduced amounts of infrastructure (adding further social and environmental benefits). What does an integrated approach mean? It does not sound like rocket science – for example: considering connection options other than point-to-point offshore network connections, such as multi-terminal meshed HVDC and HVAC options, or considering the onshore system as part of offshore development, rather than looking at onshore and offshore network designs separately. The possible results (by 2030) of going for earlier integration, as shown in Figure 2 (page 19) of the report, make for a strikingly less cluttered map. NG ESO identifies a number of regulatory changes that would be required to enable earlier integration and make recommendations to the offshore transmission review. A Phase 2 report will be issued in 2021.

- One area in which there may be an early chance to explore new approaches to offshore transmission, particularly given the provisions on UK-EU cooperation in renewable energy contained in the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement announced on 24 December 2020, is hybrid projects involving both export from an offshore wind farm and an interconnector, possibly with the Netherlands. Notwithstanding Brexit, there is enthusiasm for more interconnectors in the White Paper – potentially 18GW of interconnector capacity by 2030 (three times current levels). Alongside the White Paper, the results of a study by Aurora Energy Research are published. They find that “an increase in interconnector capacity between GB and EU would likely lead to: a decrease in emissions in GB and EU; a reduction in total power market cost in GB, as baseload prices in GB decrease; less thermal generation in GB, with little change in thermal generation in the EU; and less curtailment of renewable energy sources (RES) technologies”. What’s not to like? Of course, at present, Ofgem has more influence than ministers in determining whether new interconnector schemes go ahead, through the “cap and floor” funding regime. The White Paper does not suggest any specific policy initiative on interconnectors beyond exploration of hybrid links.

- In keeping with the paragraphs quoted above suggesting potentially significant changes in the regulatory architecture, the White Paper promises for spring 2021 a Smart Systems Plan and consultation on ensuring that “institutional arrangements governing the energy system are fit for purpose for the long term” and a dialogue on “the future of gas as we transition to a clean energy system”. Another idea that has been dormant for a while has reappeared in the promise to consult on a Strategy and Policy Statement (SPS) for Ofgem – a strategic steer to the independent regulator from ministers that was legislated for in 2013, with a draft SPS consulted on five years ago. It will be interesting to see how much government thinking has changed in this area.

- Modern energy systems are at least as much about data as pipes and wires. An energy data and digitalisation strategy is promised for spring 2021. Later in the year, the prototype of a national energy data catalogue will be launched, and Ofgem will consult on guidance about appropriate sharing of data by market participants, and associated licence conditions.

- The scheduled review of the Capacity Market in 2024 is also confirmed.

Supporting analysis/other documents published with the White Paper

Three important system-related documents are published alongside the White Paper.

- Some may find that the title Electrical engineering standards: independent review suggests content that is not the most exciting in this suite of publications. They would be wrong. This has turned out to be a very wide-ranging piece of work. It concludes that there is a need to rethink some of the most basic propositions underlying the current electricity system. These reflect the one-size-fits-all, top-down approach of a nationalised industry, where electricity was used in more homogeneous ways than it is today, and consumers were purely passive. A lot has changed in 80 years, but rules on voltage limits or assumptions about the value of lost load have not kept pace with shifts in technology and consumer behaviour. The recommendations of the panel conducting the review include reframing the system of standards around what customers can expect from the system, and what they are expected to provide in return. For example, would you be prepared to pay less for a network connection if you have a battery that can keep your lights on if it suits the system operator to interrupt your supply from the grid? How far does it make sense to oversize new network connections, given possible changes in electricity use in a net zero world? This is a huge area, and there is significant money at stake. The review quotes studies that have found that reforming standards could generate savings of £2-6 billion annually and £5-10 billion on a one-off basis.

- The summary of responses to the July 2019 consultation on Reforming the energy industry codes does not give away much in terms of government thinking on the subject. As the White Paper says: “We will consider the best future framework for energy codes and consult on options for reform in 2021, building on the government and Ofgem’s joint review of code governance and the work of the independent panel on engineering standards.” As the summary of responses puts it: “We are…aware that reforms to code governance interact with wider questions of system governance, including the current split of responsibilities across Ofgem, the system operator and government. Government are currently undertaking thinking in this area…To achieve the aims set out in last year’s consultation we expect that implementation of reforms will take a number of years, and that the delivery of some elements may need to be staged”. In other words, this is important stuff; do not hold your breath.

- In a Letter to Ofgem on RIIO-ED2 related energy policies (sent in October 2020, but only published now), Energy Minister Kwasi Kwarteng sets out some “observations” for the benefit of Ofgem as it moves forward with the RIIO-ED2 price control for electricity distribution network operators. This carefully drafted document has to navigate both the fact that government thinking in a number of the areas discussed appears to be still at a formative stage and the need not to trespass on Ofgem’s independence. Amongst other things, it encourages Ofgem to draw “clear distinctions between network operation and system operation activities” without excluding “any particular future institutional model”; and to adopt a “touch the network once” approach to investment wherever possible. There will no doubt be plenty of argument with the DNOs during the price control review process about the extent to which paying for investment in anticipation of, for example, projected take-up of EVs is justified, regardless of whether it is believed (or has been stated) that government would prefer to see formal separation of system operator and network operation at distribution level (mirroring or going beyond what the creation of NG ESO has achieved at transmission level).

Transport

Transport accounts for a quarter of UK greenhouse gas emissions, with more than 90% of it from road use. The White Paper does not give transport a chapter of its own: instead, it gets a section at the end of the Energy Systems chapter. Alongside reminders of points already set out in the TPP, such as support for clean buses and EV charging infrastructure, the main message is that a Department for Transport, Transport Decarbonisation Plan (TDP) will appear in spring 2021.

The TDP will focus on six strategic priorities: accelerating modal shift to “public transport and active travel [cycling and walking)]”; looking at “place-based solutions” to the problem of high emissions; decarbonising logistics (a timely emphasis for those of us worried about the carbon footprint of our online shopping habits); decarbonising vehicles; the UK as a hub for green transport technology and innovation; and action on the international front.

There will be a consultation in 2021 on fleshing out the plans, already announced, to end sales of new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030, while the sale of cars and vans “that emit from the tailpipe [but] have significant zero emission capability” continues until 2035.

Chapter 4 – Buildings

Key messages

There is competition for the title of Cinderella of energy policy, but the area of “buildings” has a fair claim. Will it be going to the Ball any time soon?

As the White Paper reminds us, the UK’s buildings are its second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions (behind transport, and just ahead of industry). This is not surprising, as 90% use fossil fuels for heating, cooking and hot water, and 66% of homes have an energy performance certificate rating of D or worse (the residential sector accounts for more than three-quarters of emissions from buildings). The government wants “as many [homes] as possible” to be rated C or better by 2035, as part of a drive to reduce building emissions five times as much by 2050 as we have since 1990.

Existing initiatives, such as ECO and WHD, which are being extended to 2026, with additional funding, will play an important part. A Future Homes Standard will apply to new-build properties, ensuring that they have 75 to 80% lower emissions and are “zero-carbon ready”. In the meantime, there is to be an “interim uplift in standards” to reduce emissions by 31%. Alongside greater energy efficiency both in new buildings and applied through retrofitting, heating needs to be decarbonised. There is no single technology alternative to gas boilers: heat pumps, hydrogen and green gas are all in the mix. In introducing new technology, the aim will be to “target the point of least disruption to consumers and minimise the impact on the housing market and therefore look to use natural trigger points, such as the replacement cycle for existing heating systems”. As a start, the government has already introduced the Green Homes Grant scheme for home energy improvements in England.

Policy pipeline

There is a long list of items on the agenda for 2021. We have tried to group them thematically below.

- Strategies:A Heat and Buildings Strategy will set out “ambitious plans in further detail, including the suite of policy levers that we will use to encourage consumers and businesses to make the transition [to low carbon heat]”. “Early” or “spring” 2021 will also see the launches of an Updated Fuel Poverty Strategy for England; a “world-class energy-related products policy”; and a green jobs taskforce (to green and manage the transition for those working in high carbon industries).

- Energy efficiency: There will be a consultation on a performance-based rating scheme for large commercial and industrial buildings. The government will also consult on a scheme to facilitate the installation of efficiency measures by small businesses, either through an auction process or an energy efficiency obligation. There will also be consultation on strengthening the existing ESOS regime, based on options identified in the post-implementation review of that scheme. If changes are needed to the Energy Performance of Buildings (England and Wales) Regulations 2012, as they may be, the power under which those regulations were made is no longer available after the end of the Brexit transition period, and the government will have to wait until Parliamentary time allows for new enabling legislation to be made.

- More consultations:Significant consumer expenditure on home energy improvements that is not covered by regulated support schemes is likely in many cases to be financed by borrowing, as part of existing mortgage arrangements. There will be a consultation on how mortgage lenders could support homeowners in improving the energy performance of their homes. Consultations will take place on regulations to phase out fossil fuels in off-grid buildings, and on whether it is appropriate to end gas grid connections to new homes built from 2025. As well as responding to the April 2020 consultation on proposals for a Clean Heat Grant to support heat pump installation, the government will consult on ways of supporting the development of the UK heat pump market, including voluntary uptake by consumers in on-grid homes.

- Responses to consultations:Responses are promised to the April 2020 proposals for a Clean Heat Grant and a green gas support scheme, which is scheduled to launch in autumn 2021. The aim is to reach treble 2018 levels of biomethane injection into the gas grid by 2030.

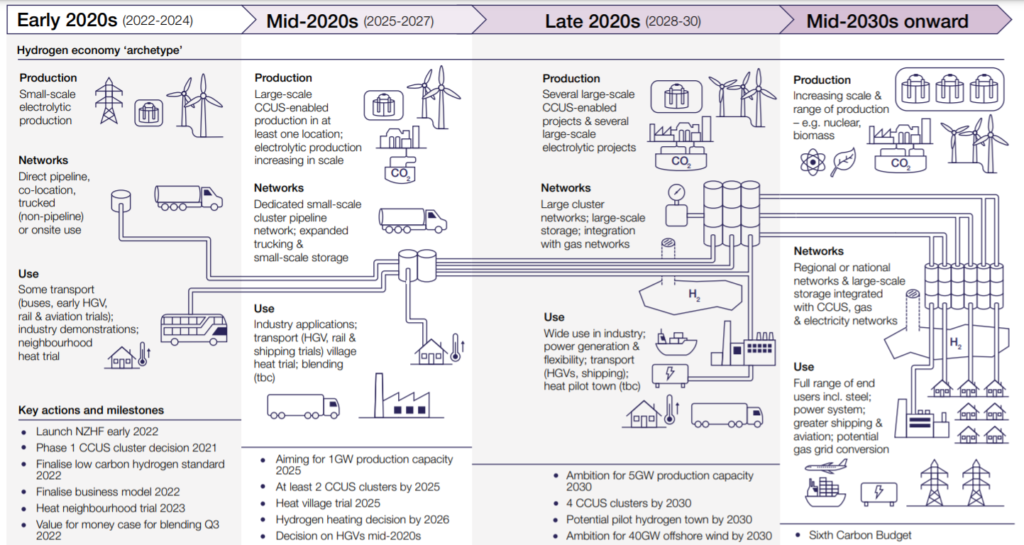

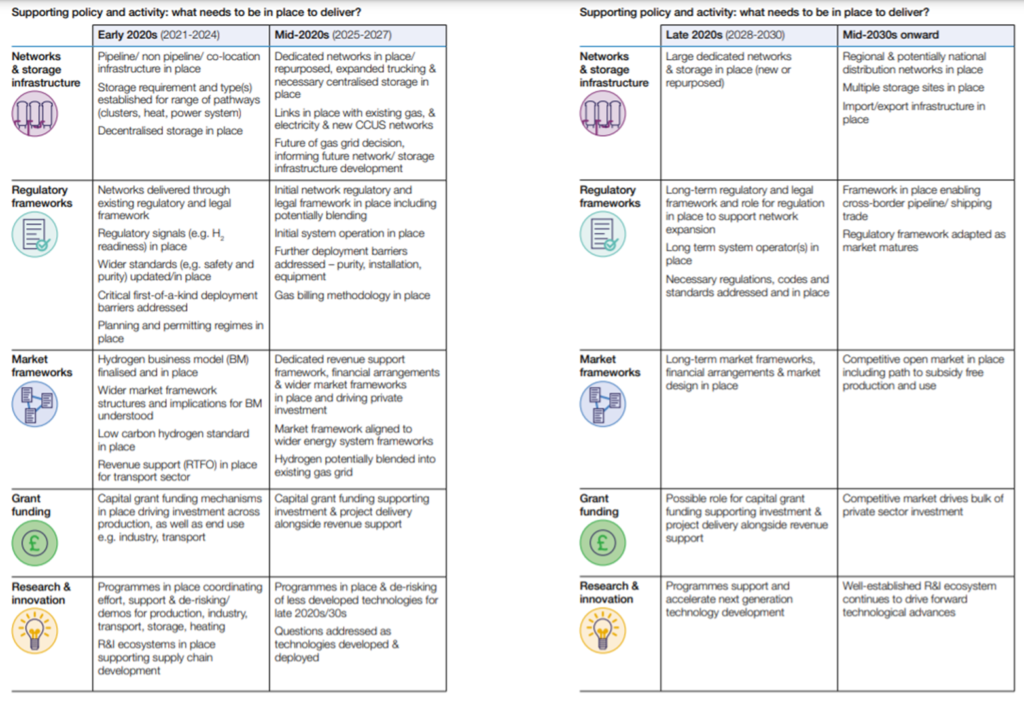

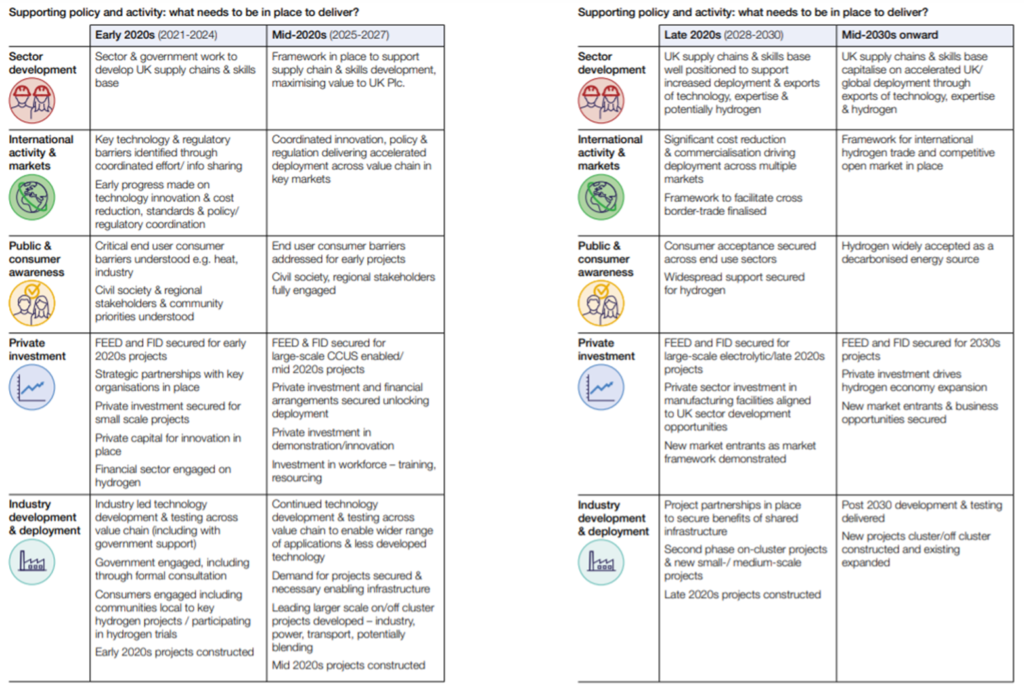

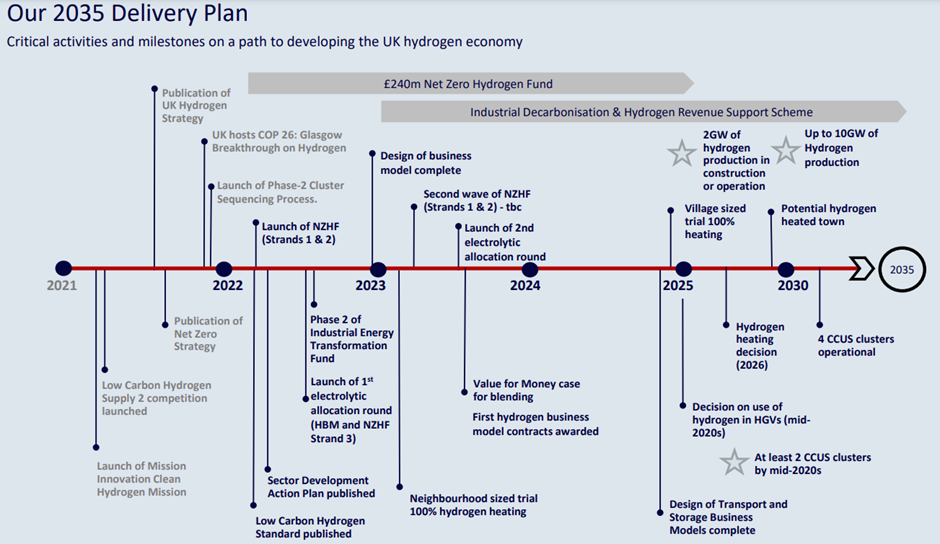

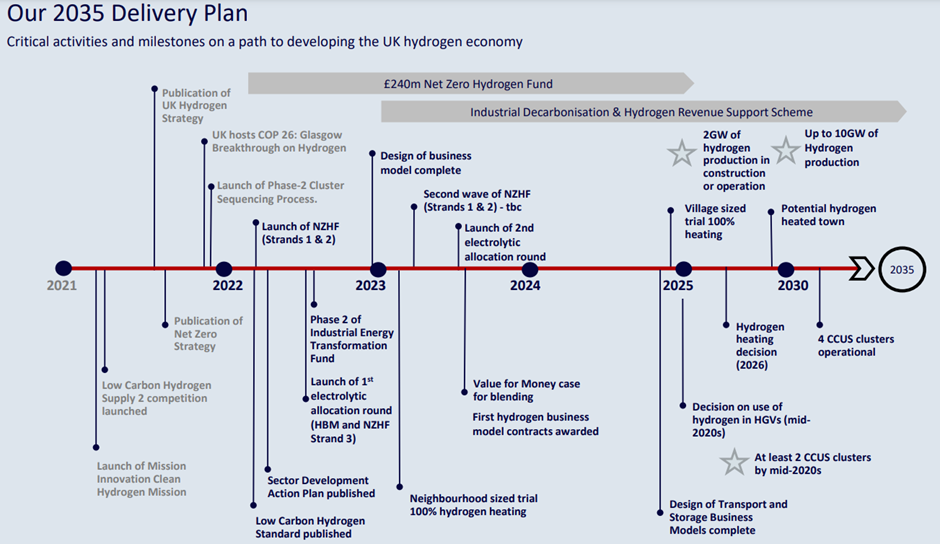

- Hydrogen and green gas: Building on existing trials of hydrogen in the context of domestic heating and other applications, there will be a neighbourhood level trial by 2023 and a “hydrogen village” by 2025. Strategic decisions about the long-term role of hydrogen in heating should be addressed in the mid-2020s and a “hydrogen town” be seen by the end of 2020. There will be a call for evidence on hydrogen-ready appliances during 2021, and steps will be taken to enable blending of up to 20% hydrogen in the gas grid – which has already been demonstrated to be technically feasible – by 2023, subject to further trials.

- Heat networks:Converting homes and businesses to low carbon forms of heating is easier if they are supplied by a heat network, rather than all having their own gas-fired boilers. Installing a network also enables other energy efficiency savings to be made. The government has encouraged heat networks through the Heat Networks Investment Project and proposes to continue to do so through the Green Heat Networks Fund. However, there is a consensus that, in order to reach their full potential, heat networks need their own scheme of regulation. The government consulted on this in February 2020 and now proposes to legislate on it “in this Parliament”, as well as taking powers to reduce the reliance of existing heat networks on gas as a fuel. The Scottish Government has already introduced its own legislative proposals (on somewhat different principles) in this area. There will be a consultation on heat network zoning (in England and Wales), with the aim that local authorities should designate heat network zones by 2025.

- Innovation:The government will explore options for enabling permanent electricity demand reduction to be a viable alternative to building more generation or network capacity. This could involve thermal, hot water or battery storage, possibly combined with time of use tariffs.

Supporting analysis/other documents published with the White Paper

In commenting on the TPP, we noted that the government envisages increasing heat pump installation rates in the UK by a factor of 20. Alongside the White Paper, it published the results of a Heat pump manufacturing supply chain research project, which investigated the supply chain aspects of increased UK use of heat pumps. In particular, this looked at the potential to convert additional heat pump demand into more jobs in the UK heat pump manufacturing sector – some of them potentially replacing jobs that may be lost when gas boilers are no longer installed in new homes (from 2025).

Chapter 5 – Industrial energy

Key messages

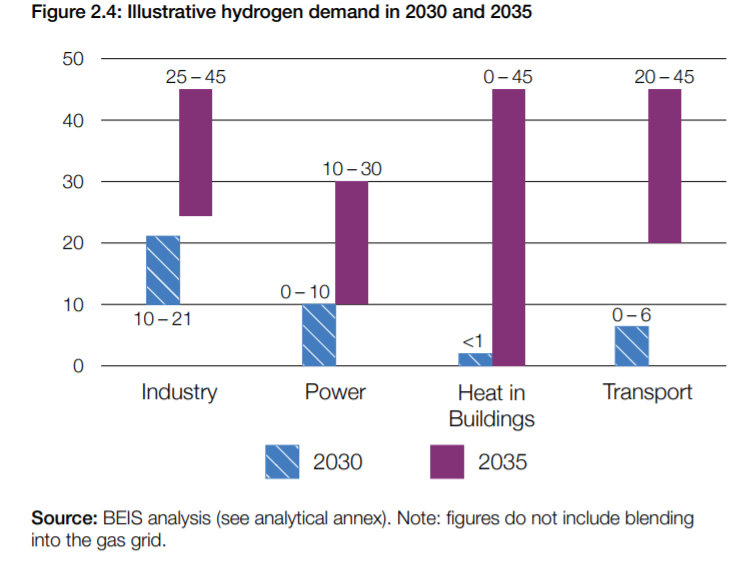

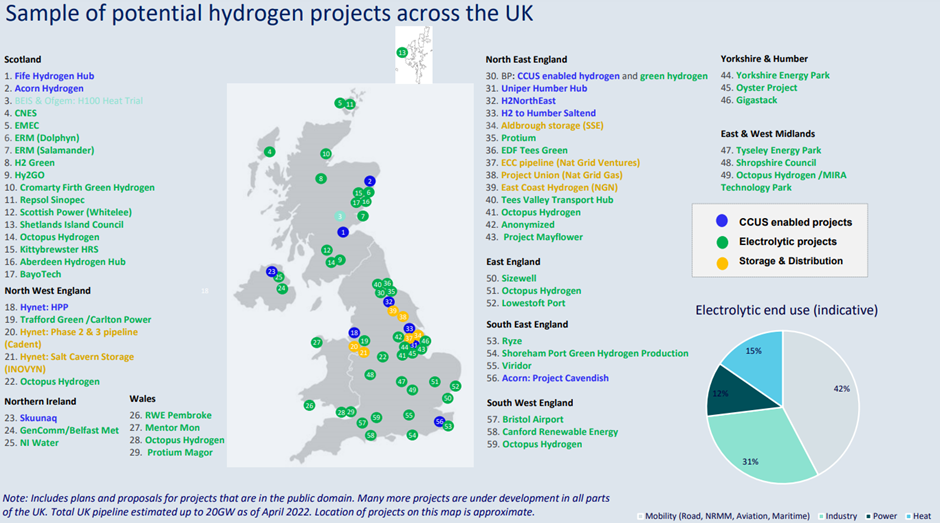

The centrepiece of the government’s industrial decarbonisation strategy is CCUS. The TPP signalled an increase in ambition for supporting CCUS clusters from two to four by 2030. The White Paper additionally refers to “at least one fully net zero cluster by 2040”. Hydrogen is also seen as playing a key part, and the White Paper mentions the target of 5GW of low carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030 and the Net Zero Hydrogen Fund (“£240 million of capital co-investment out to 2024/25”) that were set out in the TPP. Elsewhere, the White Paper indicates that the government is interested in encouraging more forms of low carbon hydrogen production than what are usually referred to as “blue” (methane reforming with CCUS) and “green” (renewable electricity electrolysing water) hydrogen – for example, biomass gasification and use of nuclear power.

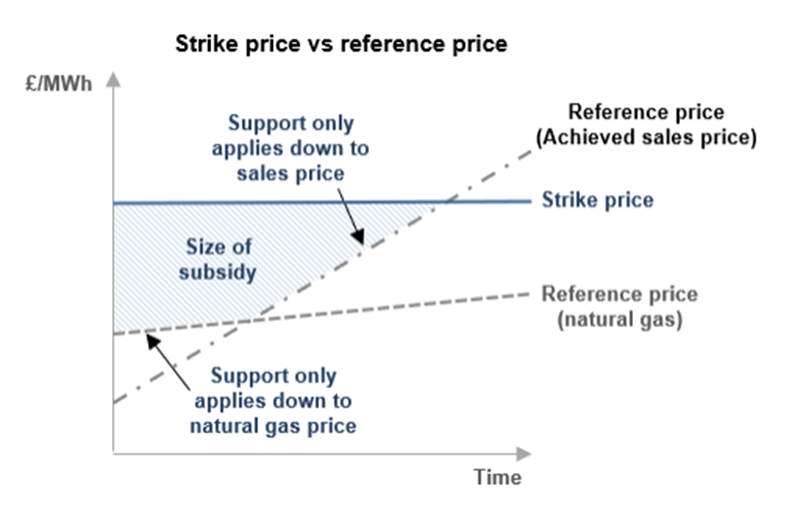

Any serious support framework for industrial CCUS or low carbon hydrogen projects needs at least to take into account applicable carbon pricing regimes. The higher carbon prices are, the smaller the subsidy, in principle, that users of CCUS facilities or low carbon hydrogen require, because high carbon alternatives will have become more expensive. Indeed, the value of avoided emissions, based on carbon pricing, is likely to be a key component in calculating CCUS and hydrogen subsidy payments. Confirmation that a UK ETS will take effect from 1 January 2021 in GB is therefore welcome (Northern Ireland remains subject to the EU ETS under the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement).

The UK ETS has already been the subject of consultation. It is very similar to the EU ETS that it replaces, except in its insularity, although the UK remains “open to linking the UK ETS internationally”. An Auction Reserve Price is included to provide a price floor when emitters bid for the allowances that those covered by the scheme need in order to be permitted to emit greenhouse gases. In principle, by making use of this and other features of the scheme, it may be possible for it to provide a more certain trajectory of future carbon prices than the EU ETS has sometimes done in the past.

However, neither the EU ETS nor the UK ETS will stand still in the next few years. For example, the scope of both schemes is likely to be expanded to cover businesses and sectors that are currently outside it. The government is also interested in exploring the possibility of using the UK ETS to incentivise the deployment of greenhouse gas removal technologies.

Policy pipeline

The policy agenda set for 2021 is as follows (in the order suggested by the White Paper):

- publication of a hydrogen strategy (Scotland has stolen a march on the UK here);

- publication of an Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy (spring 2021);

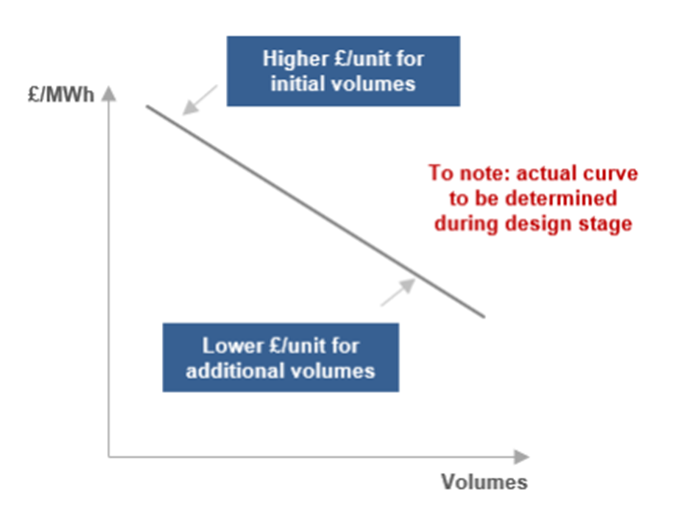

- consultation on a preferred business model for low carbon hydrogen in 2021, introducing a commercial framework by 2022;

- publication of further details on revenue mechanisms for CCUS, to be finalised by 2022.

Other documents published with the White Paper/immediate follow-up Alongside the White Paper, the government published a summary of responses to its August 2019 Creating a Clean Steel Fund: call for evidence. This document reflects both the importance, and some of the complexities, of decarbonising the steel sector. A few days later, the CCUS update offered some insights into the government’s evolving thinking on CCUS for industrial emitters (a subject that we had previously discussed in a November 2020 article). Perhaps inevitably, this is less developed than the business model for CCUS power discussed above. However, chapter 5 of the main update document and its Annex E give us more information than we had already about the central payment mechanism and contract structure for supporting industrial CCUS (drawing again on the existing EMR CfD model), as well as other key features such as eligibility, metering and risk allocation.

Chapter 6 – Oil and gas

Key messages

The UK’s oil and gas sector, centred on the North Sea, has a key part to play in the Energy Transition. The sector’s upstream regulator, the Oil and Gas Authority (OGA) has been emphasising the “net zero” agenda for some time, and there has been no shortage of recent studies of the potential for integrating the North Sea’s “old energy” economy of oil and gas extraction with its “new energy” economies of offshore wind, CCUS and low carbon hydrogen.

The question is what it does or should mean for the North Sea to be “net zero” by 2050 (an aim previously stated by the OGA and repeated by the White Paper). Depending on how it is defined, this could be a much harder goal to grasp or achieve than, say, decarbonising the UK power sector – given the range of emissions impacts of the oil and gas industry (both in its own activities, and upstream and downstream of those).

The OGA consulted in May 2020 on proposed revisions to its governing Strategy that are designed to ensure that the oil and gas industry facilitates the new technologies and does its best to reduce emissions produced by venting, flaring and the supply of power from on-platform combustion units. We have written about this elsewhere (see here, here, here, here, here and here).

Earlier in December 2020, Denmark announced its intention not to issue any more upstream licences, and to aim to end all existing production in its part of the North Sea by 2050. The UK’s vision remains different. The White Paper indicates that, while a return to “business as usual” after the COVID-19 emergency is not an option, ensuring that the UK remains an attractive destination for global capital is seen as the best way to secure an orderly and successful transition away from traditional fossil fuels.

However, there will be a review of policy on future upstream licensing, seeking to ensure its compatibility with net zero. This is presented as an “opportunity for the UK to demonstrate that effective climate leadership can be compatible with maintaining a strong economy and robust energy security”. It may involve “seeking independent advice on how proceeding with future licensing would impact our climate and energy goals”.

Meanwhile, the UK will join the World Bank’s “zero flaring by 2030” initiative. The OGA will benchmark greenhouse gas emissions to drive performance and create a new asset stewardship expectation for net zero. It will update its guidance and economic assessments to include full carbon costs. The government will tackle regulatory and policy barriers to the use of clean electricity on platforms. It will challenge industry players to address embodied “Scope 3” emissions both upstream (in its own supply chains) and downstream (among those who use its products) of their own activities. Future government support will depend on the sector adopting “meaningful measures which reduce emissions and report[ing] transparently on progress, for example through adhering to the recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure”.

On the decommissioning side, the White Paper signals an intention to work with industry and regulators on regulations for re-purposing assets and to develop technical guidance on how to do this safely and securely. There is to be a review of the decommissioning regulatory unit OPRED to ensure that it is fully equipped to drive up environmental standards.

The White Paper sets out the UK’s new policy, announced a few days before its publication, of no new direct financial or promotional support for the fossil fuel energy sector overseas. There are to be some “tightly bound” exemptions for activities that support health, safety and environmental improvements; form part of wider clean energy transitions; support decommissioning or are associated with a humanitarian response.

Policy pipeline

The agenda set out for 2021 is as follows:

- conclusions on the licensing regime will be published;

- a North Sea Transition Deal will deliver “new business opportunities, jobs and skills [in] the sector [and] protect the wider communities which rely on the oil and gas sector”;

- a draft Downstream Oil Resilience Bill will be published, with a view to ensuring “a secure and resilient supply of fossil fuels during the transition to net zero emissions”;

- there will be a consultation on the use of fuels from non-biogenic waste (such as non-recyclable plastics).

Other documents published with the White Paper/immediate follow-up

Alongside the White Paper, the government published a response to Strengthening the UK’s offshore oil and gas decommissioning industry: call for evidence. The focus here is on improving the competitiveness of the UK’s decommissioning sector, and increasing its export business. There is an emphasis on visibility of the pipeline of projects and benchmarking. Stakeholders pointed out the lack of UK heavy lifting vessels and ultra-deep-water ports, but are said to have urged the government to avoid forms of intervention that could result in marked distortions. Some useful next steps are noted.

Two days after the White Paper was published, the first policy deliverable it identified in the oil and gas space was delivered, in the form of a final version of the revised OGA Strategy, for laying before Parliament. This final version is essentially identical to the version that accompanied the consultation in May 2020, with only a small number of minor drafting changes from that version.

Conclusions

The wait for the White Paper began some three years ago, under a different Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, and a different Prime Minister. At around the same time, that Secretary of State had commissioned an independent review of the cost of energy which resulted in the economist Dieter Helm making wide-ranging and often quite radical recommendations about almost all the areas of energy policy now covered by the White Paper.

It is questionable whether anybody ever expected the White Paper to translate Helm’s vision into a programme of legislative and regulatory action, and it does not. However, it does show clear evidence of government thinking across the whole of energy and the sectors most affected by climate policy, and having serious plans, some of which could take a radical turn as they develop, to address the issues that its net zero agenda requires to be addressed as a matter of urgency.

There can be no doubt that, for obvious reasons, UK energy policy has developed more slowly than was desirable over the last four and a half years. However, there does appear now to be a fairly clear plan for how to make up the lost time. That does not guarantee that the execution will follow, but it is a good start, and we now have a much firmer and more detailed schedule, produced by the government itself, against which to measure its performance over the coming years. The progress that has already been made in some areas, such as parts of CCUS policy, shows what can be achieved at pace.

The next big domestic test of the government’s ambition, of course, will be its response – also due in 2021 – to the Committee on Climate Change’s recommendations on the Sixth Carbon Budget. Further events in the political timetable, notably the UK’s leadership of the G7 in 2021, and, of course, its hosting of COP26 in November 2021, can be expected to drive imperatives for major delivery milestones to be met at or before each event. 2021 is indeed set to be a busy year!

Subscribe and stay updated

Receive our latest blog posts by email.