The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) has unveiled in a consultation proposals for a Green Gas Support Scheme, providing support for injecting biomethane into the grid, and a Clean Heat Grant Scheme, offering grants of up to £4,000 to encourage uptake of heat pumps, and in some cases biomass heating. Entitled Future support for low carbon heat, the consultation is one of three linked documents published together on 28 April 2020 which between them set out how BEIS proposes to replace the Renewable Heat Incentive (theRHI) in the short term. The consultation is scheduled to close on 7 July.

Background

The UK is the first major economy in the world to set a legally binding target to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Currently, heating the UK’s homes, businesses and industry, dominated by the burning of fossil fuel, is responsible for approximately one third of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions.[1] In its report to government that led to the adoption of the net zero target in 2019, the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) highlighted the scale of the challenge that the UK faces in decarbonising heat: currently, the share of heat demand met by low carbon heating needs to increase from around 4.5% today to around 90% in 2050.

Successive UK governments have adopted a number of measures designed to enhance the energy efficiency of buildings (thereby reducing heat demand) and to encourage the installation of more efficient and lower carbon heating equipment. Heat policy is necessarily a complex jigsaw, with important aspects ranging from planning, agricultural and waste policy to industrial strategy, but the RHI has been at the forefront of government heat policy now for some 10 years. It aims to encourage the production of biomethane (enabling the supply of gas through the gas grid to become “greener”) and the installation of low carbon heating equipment such as heat pumps and biomass boilers.

The intention was that the RHI would do for renewable heating technologies what subsidies for renewable electricity generation (like the UK’s Renewables Obligation and Feed-in Tariffs regimes, and their counterparts in other jurisdictions) have done for solar panels and wind turbines: make installing them financially attractive to a mass market, thereby stimulating demand and bringing costs down, allowing subsidy costs to decline over time and demand to increase in a virtuous circle. However, it has not proved easy to replicate in the heat sector what worked so well in the power sector.

The RHI has done much to build the supply chains for a range of low carbon heating technologies, but it cannot be said to have had a transformative effect on the market.

- At a high level, in the words of the CCC’s net zero report: “Over ten years after the Climate Change Act was passed, there is still no serious plan for decarbonising UK heating systems and no large-scale trials have begun for either heat pumps or hydrogen.”

- More specifically, the RHI has been criticised for failure to provide value for money, and falling short of the levels of deployment that it was originally expected to achieve (see in particular the 2018 report of House of Commons Public Accounts Committee (PAC) on the RHI).[2]

- Whilst an incentive scheme like the RHI is only one element in determining the uptake of low carbon heating technologies, and all national energy markets are different, the UK’s recent performance in this area is not particularly impressive by European standards. In 2018, 10 times as many heat pumps were purchased in France as in the UK, while Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland, whose combined population is less than half that of the UK, purchased more than 13 times as many heat pumps as the UK between them.[3]

Renewable Heat Incentive

The RHI is a UK government scheme established to encourage uptake of and investment in low carbon heat technologies through financial incentives. It is the first renewable heat incentive scheme in the world. There are separate schemes for domestic and commercial projects, that were introduced in 2011 and 2014, respectively. The RHI provides quarterly payments to individuals or organisations for the generation of heat from several different renewable energy sources, including biomass boilers and plants, ground source heat pumps, water source heat pumps and solar thermal or (for non-domestic RHI) injecting biomethane into the gas grid.

Under the RHI, Ofgem pays quarterly support payments to participants for a period of seven years (for Domestic RHI) or 20 years (for Non-Domestic RHI). The payments are calculated according to the particular RHI tariff that applies to the installation at the time it was installed. Such payment is intended to cover the additional capital and running costs of renewable heat installations (compared to traditional installations). The government initially set the level of tariffs to achieve a 12% rate of return on additional capital invested (except for solar thermal).

Some notable features of the RHI are:

- Tariff guarantees, which allow RHI applicants to secure a tariff rate before an installation is commissioned and fully accredited by Ofgem or before biomethane for injection into the grid has been produced.

- RHI payment rates are subject to a degression mechanism (if triggered), a pre-determined monthly downward adjustment of tariff levels for new installations where uptake of RHI technologies is greater than forecast. This cost control measure is intended to bring deployment down so that it is within anticipated levels.

- Non-domestic RHI payments cannot be assigned and transferred to allow a third party (e.g. a lender) to directly receive the payments, unless there is a change of ownership.

Seen from the perspective of the consumer of heat, the RHI has a number of drawbacks – or perhaps it would be fairer to say that it does not go far enough to overcome the factors that may inhibit take-up of technologies such as heat pumps.

- Beyond the satisfaction of “being green”, consumers’ decisions to switch to renewable heat are likely to be influenced by the prospect of saving money by switching to low carbon heat. They will only have this if they first replace their existing equipment (typically a gas boiler) withrenewable technology, and then make savings that pay back the capital cost of the new equipment over a period that makes sense to them.

- The RHI makes no upfront contribution to the costs of equipment purchase and installation, which consumers must incur before they can be eligible for RHI payments.

- Consumers’ calculations of potential payback will therefore have to be based entirely on their anticipated levels of RHI payments over time: how many years will it take to get their money back? The answer is that they cannot always be certain. There are a number of potential complexities involved in making the necessary calculations under the RHI, and until consumers receive accreditation from Ofgem, they cannot be sure that they will in fact receive the particular level of payments on which they may have based their calculations when deciding to move to renewable heating and enter into any associated financing for the purchase of equipment.[4]

The RHI was due to close to new applications on 31 March 2021, but in the March 2020 budget it was announced that the closure date for the Domestic RHI would be deferred until 31 March 2022. The Non-Domestic RHI will close to new applications on 31 March 2021. This was confirmed in a notice published alongside the consultation. A second consultation published at the same time sets out further detail on the closure of the Non-Domestic RHI and other aspects of its future operation (including a third allocation of tariff guarantees with a flexible commissioning deadline). In the remainder of this post, we focus on the consultation about the schemes that will replace the RHI.[5]

The proposals

BEIS’s consultation introduces proposals (the Proposals) for a Green Gas Support Scheme and a Clean Heat Grant, each mirroring aspects of the current RHI scheme. In broad terms:

- the Green Gas Support Scheme replaces the Non-Domestic RHI in so far as it has been a supply-side measure relating to the production of biomethane, and is similar in structure to the RHI in that it would involve the payment of a tariff per kWh of gas; and

- the Clean Heat Grant replaces the Non-Domestic and Domestic RHI as a demand-side subsidy for heat pumps and biomass heating, but rather than providing payments per kWh of renewable heat, it would take the form of a (probably) capped grant towards the cost of purchasing and installing the equipment, rather than payments per kWh of renewable heat.

Green Gas Support Scheme

Biomethane injection into the gas grid accelerates the decarbonisation of gas supplies, and is a necessary step towards meeting the UK’s net zero greenhouse gas emissions target. The proposed Green Gas Support Scheme seeks to increase the proportion of green gas in the grid through support for injection of biomethane produced through anaerobic digestion (AD). The potential importance of biomethane can be seen from the estimates made in a report prepared for the Energy Networks Association (ENA) in 2019 (Pathways to Net-zero: Decarbonising the Gas Networks in Great Britain). Looking at what the position might be in 2050, this considered a “Balanced Scenario”, where “[g]as demand volumes are approximately 50% of present levels with hydrogen and biomethane supplying 240 TWh and 200 TWh respectively” and an “Electrified Scenario”, where “gas plays a more limited role delivering a combined 220 TWh of energy demand between hydrogen and biomethane, equivalent to 25% of today’s gas volumes” (but still a lot of biomethane). To put these figures in context, in 2018, biomethane accounted for 0.4% of UK gas supply.

The proposed scheme focuses support on biomethane because currently biomethane is the only green gas commercially produced in the UK. However, BEIS acknowledges that to further decarbonise the gas grid, it may be appropriate to widen support to other green gases in the longer term and therefore invites views on what mechanisms might be appropriate for longer-term green gas support, and on the potential for including alternative sources of green gas, such as hydrogen blending, in the future. One advantage of biomethane is that its physical properties are more or less the same as those of methane from natural gas. Accordingly, introducing it into the gas grid does not require the kinds of significant commercial and regulatory changes that would be likely to be required to take account of hydrogen blending (hydrogen and methane being very different molecules).

Tariff tiers and periods

BEIS highlights in the Proposals the need to balance incentivising continued AD deployment and delivering value for money to taxpayers. To incentivise AD deployment, a three-tier tariff mechanism for AD plants, which closely mirrors the RHI tariff mechanism, is proposed. This is based on volumes of gas injected into the grid and aims to reflect the different costs of producing different volumes of biomethane. Under the RHI scheme, the highest tariff is available for the first 40,000 MWh of eligible biomethane injected into the grid over a 12-month period (Tier 1). BEIS understands that, in AD plants that have been commissioned since RHI tiering was introduced, more than 90% of biomethane is produced under Tier 1. To encourage the development of larger AD plants that can achieve better economies of scale, under the Green Gas Support Scheme BEIS proposes to increase the Tier 1 limit to 60,000 MWh.

However, to lower total costs and ensure better value for public money, and to reflect developments in AD technology, BEIS is exploring the possibility of a 10- to 12-year tariff period (the RHI period is 20 years). A shorter tariff period may run the risk of undermining the principle of encouraging investment in AD deployment, given that an insufficient tariff period could impact project bankability and discourage AD plant developers by potentially rendering debt repayments unmanageable.

Tariff changes and guarantee budget cap

The Proposals aim to retain a degression mechanism, building on the mechanism under the RHI. However, BEIS aims to make the mechanism more cost-effective and suggests adjusting the frequency and size of degressions. Although degression under the RHI, alongside tariff guarantees, provided some certainty for investors, it is worth noting that the biomethane tariff has also been reduced outside the degression mechanism a number of times.

BEIS proposes to replicate the RHI tariff guarantee mechanism. However, a tariff guarantee budget cap is also proposed to temporarily halt new tariff guarantee approvals if the cap is reached.

As the impact assessment that accompanies the consultation points out, payments under the scheme are not the only revenue stream for AD plants producing biomethane. They are assumed to receive a payment for their gas (at market rates) and – to the extent that they use waste as a feedstock – they will also receive a “gate fee” (although the impact assessment indicates that it may be difficult for individual plants to secure long-term fixed-price contracts with waste contractors). There is also an emerging market in green gas certificates (not, as yet, it would appear backed on the demand-side by any particularly strong segment of consumer demand specifically for green gas).

Waste feedstock requirements and sustainability

In general, BEIS intends to reflect the existing RHI sustainability criteria (as they apply to feedstock for biomethane) in the Green Gas Support Scheme. However, the consultation document also raises two questions about these criteria.

The Proposals stress the advantages of food waste as a feedstock for AD plants, due to the significant carbon savings achieved by reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the waste compared, for example, to sending it to landfill. Further, diverting food waste to AD contributes to England meeting its target to work towards eliminating food waste to landfill by 2030. While the Proposals acknowledge the fluctuating nature of food waste and cite energy crops (a key alternative feedstock, along with sewage and manure) as having practical importance for many biomethane producers by providing a stable feedstock supply and producing a higher yield of biogas, the Proposals state that BEIS is keen to promote the use of waste feedstocks due to the greater environmental benefits.

The Proposals refer to separate food waste collections in Wales and Scotland and the recently published Environment Bill, which would require that every household and business in England has a separate collection for food waste, so that this can be recycled. BEIS expects the Environment Bill measures to commence from 2023 and that this will significantly increase the amount of separately collected food waste available for AD.

However, having made all these points, the Proposals do not definitely propose an increase on the proportion of biomethane feedstock that is required to be made up of waste under the RHI (50%). They simply ask for views on whether it should be increased under the new scheme, and if so what a suitable new figure should be.

The second question is a more technical one: whether the new scheme should mirror the sustainability criteria of the revised EU Renewables Directive (RED II). Not doing so could be an early exploitation of the freedom to depart from previously binding EU rules following Brexit.

Green Gas Levy

Like the March 2020 Budget, the consultation states that the Green Gas Support Scheme will be funded by a Green Gas Levy. This is to be the subject of further consultation, and the present consultation does not disclose any further details.

The funding of the scheme is of some importance. The RHI has been funded directly by government and therefore effectively by taxpayers rather than by energy bill-payers via a levy on licensed suppliers, as has been the case with most of the UK’s electricity subsidy programmes.

The imposition of such levies on electricity suppliers has been a material factor in the retail price of electricity in a way that has not really been paralleled in relation to the supply of gas. If a Green Gas Levy were added to consumer gas bills, it would probably not increase them greatly over the life of the Green Gas Support Scheme but, in the longer term and on a larger scale, measures that make gas more expensive for consumers could help to persuade them that they would save money by installing heat pumps, which run on electricity. It is worth noting in this context that the enabling powers under which the RHI legislation is made, and under which the consultation implies that the secondary legislation for the new scheme would also be made (s.100 of the Energy Act 2008), does make provision for the funding of heat subsidy payments out of a levy on “designated fossil fuel suppliers”.

A short-lived scheme?

The Green Gas Support Scheme is presented as something of a stop-gap measure, running only from 2021/22 to 2025/26. The consultation anticipates further consultation (it does not say when) on what mechanisms might be appropriate for longer-term green gas support. It raises, by way of example, the possibility of a “supplier obligation” scheme like the Renewables Obligation for electricity (under which licensed suppliers would presumably be obliged to purchase quantities of green gas proportionate to their shares of supply), and of Contracts for Difference (a model already used for low carbon electricity and possibly about to be adapted to fit the context of carbon capture and storage from non-power generating industrial emitters).

Over about 20 years, renewable subsidy regimes have helped to increase the UK’s renewable electricity generation to a point where it accounts for more than a third of UK electricity. Could the successor to the Green Gas Support Scheme have a similarly dramatic impact on the production of biomethane, and perhaps also hydrogen – as it would need to do in order to start to move towards the levels of green gas required in Net Zero scenarios contemplated in the report for ENA quoted above?

Clean Heat Grant

The Clean Heat Grant is most obviously a replacement for the Domestic RHI, which is closing to new applicants on 31 March 2022. The Clean Heat Grant Scheme is expected to begin in April 2022 with funding committed for two years, to March 2024. The scheme aims to provide support for heat pumps and in certain circumstances biomass to provide space and water heating, through an upfront capital grant to help address the barrier of upfront cost. The scheme is targeted at homes and small non-domestic buildings. Although it is in principle available in industrial and commercial contexts, the level of funding being made available is likely to mean that its main impact is on the domestic market.

BEIS proposes that the scheme will be administered by Ofgem. Like the RHI (and unlike the Green Gas Support Scheme), it would be funded directly by government (i.e. by taxpayers, not bill-payers).

The key features of the scheme are:

- delivering support through an upfront grant scheme;

- a voucher system for grant delivery, designed to target the upfront cost barrier;

- supporting domestic and non-domestic installations up to a capacity of 45 kW;

- providing a flat-rate grant across different technology types;

- a recommended support level of £4,000; and

- criteria for ensuring biomass heating is only installed in properties deemed not suitable for a heat pump.

The proposed flat rate £4,000 grant does not scale with system size or change across technology types. However, an upfront scheme would provide more certainty of funding than under the Domestic RHI. The Proposals state that this structure would allow the market to identify which technology is the most cost-effective for each property, and that it expects that for the majority of applicants this will be air-source heat pumps. £4,000 would probably not finance the whole cost of a heat pump, but it might in some cases represent about 50% or more of the cost of an air-source heat pump (one of the cheaper eligible technologies), and so should have a material impact on consumers’ calculations of payback periods.

Although the Clean Heat Grant is a welcome proposal from an upfront costs perspective, the Proposals state that BEIS will have the right to review the grant levels in response to unforeseen market changes or “if uptake falls substantially outside the expected range“. Aside from this, the Proposals introduce a number of funding controls as part of the Clean Heat Grant Scheme: the allocation of grants through quarterly grant windows and a cap on the amount of grants against a pre-agreed budget cap. These proposed limits to the grant scheme have attracted early criticism from the renewable heat industry. For example, a market participant has commented that “we were disappointed by the lack of extension for new non-domestic RHI projects and the implications the cap on the future grant scheme will have. Both of which could result in businesses being unable to finish their projects or continue to operate at a time when the industry needs to be bolstered to achieve our legally binding Net-Zero targets” [6]. Further, the proposed voucher system for the delivery of the grant will be issued on a first come, first served basis.

Focus on heat pumps

The Proposals refer to the CCC’s recommendation to increase deployment of heat pumps significantly in the 2020s to deliver its interim carbon budgets, replace high carbon fossil fuel systems off gas grid and set the UK on course for net zero emissions. The CCC has also suggested that the UK would require 15 million homes to be fitted with heat pumps or hybrid heat pumps by 2035.

The Proposals’ focus on heat pumps acknowledges their key role in decarbonising heat. The Proposals state that “heat pumps are one of the primary technologies for decarbonising heat. Looking towards 2050, heat pumps could enable us to almost completely decarbonise heat alongside the decarbonisation of electricity generation“. Further, the Proposals note that “buildings off gas grid have a large proportion of the most polluting heating from oil and coal, and will not benefit from any measures to green the gas grid” and that heat pumps are suitable for a wider range of buildings than biomass, although biomass is also supported under the scheme for buildings in which a heat pump is not suitable.

BEIS does not currently propose that process heating, biogas combustion, solar thermal, hybrid heat pump systems and heat networks will be supported by the Clean Heat Grant Scheme.

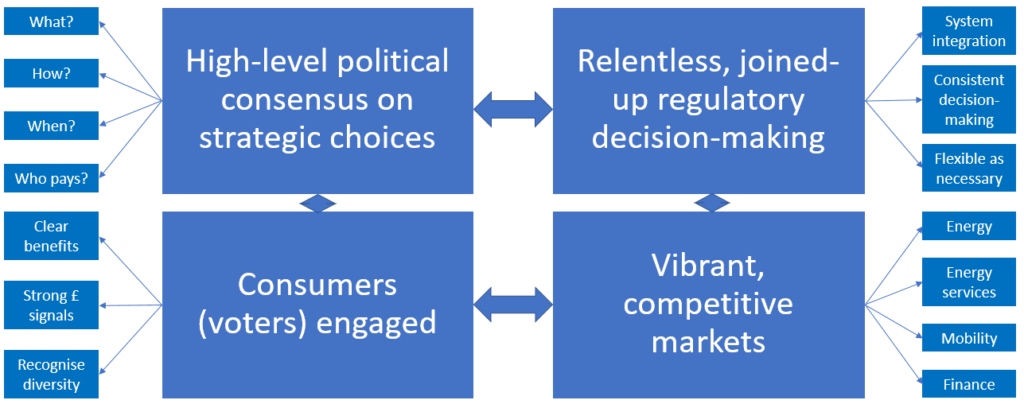

Compliance

BEIS acknowledges in the Proposals the need for “a consistent, long-term policy framework and is clear that regulations will be needed to underpin the transformation of our building stock“. In relation to the Proposals, BEIS suggests a participant compliance regime for the Green Gas Support Scheme and the Clean Heat Grant Scheme, managed by Ofgem. The compliance regime for the Green Gas Support Scheme is expected to be based closely on the existing RHI compliance regime. The compliance regime for the Clean Heat Grant Scheme is expected to differ from the current RHI regime for heat pumps and biomass, but would involve Ofgem having the ability to carry out on-site checks of eligibility, and to require remedial work or recoup grant payments in cases of non-compliance.

Next steps

The consultation is only the start of a process. New legislation will be required to establish the two new renewable heat support schemes set out in the Proposals. The experience of the RHI provides a precedent for the Green Gas Support Scheme (although not the Green Gas Levy to fund it); the Clean Heat Grant could be modelled on earlier grant-based renewable energy funding schemes. Guidance will also need to be provided, particularly on the Clean Heat Grant, to ensure that consumers understand what they are being offered. There are plenty of details to iron out (and details matter in such schemes), but there is a bit more than a year before the first scheme is expected to come into force, so it should be possible to have everything ready in good time.

However, as noted above, these two schemes are part of a much bigger emerging picture of heat policy. The consultation notes, for example, that BEIS’s Heat and Buildings Strategy, which it aims to publish later this year, will lay out the immediate actions it will take for reducing emissions from buildings, and that the Future Homes Standard, to be introduced by 2025, will require new build homes to be “future proofed” with low carbon heating and “world-leading” levels of energy efficiency.

Other live initiatives include BEIS’s proposals to regulate heat networks, and the Industrial Energy Transformation Fund, aimed at energy-intensive industries. Perhaps the most exciting prospect opened up by the consultation, though, is of discussion on the future opening up of a green gas market support scheme that could include hydrogen as well as biomethane – formidable though the technical chllenges of designing such a scheme would be.

[1] BEIS (2018) Heat decarbonisation: overview of current evidence base, Fig.2.1

[2] Paragraph 4 of the PAC report is as follows: “The Department originally expected the RHI to fund 513,000 installations by 2020 at a cost of £47 billion over the lifetime of the scheme [ending in 2041]. By the end of December 2017, more than six years after the start of the non-domestic scheme and more than three years after the start of the domestic scheme, the RHI had funded just 78,048 installations. At current rates of uptake, the scheme will fund 111,000 new installations by 2020–21, 78% less than the number initially intended. The Department expects the cost of the scheme to fall from £47 billion to £23 billion, 51% less than initially planned. The expected total renewable heat production resulting from the scheme has also been reduced by 65%, from 61 TWh to 21 TWh per year by 2020; and total carbon emissions reductions over the life of the RHI have been reduced by 44%, from 246 MtCO2e to 137 MtCO2e.”

[3] Figures from the European Heat Pump Association: see slide 12 of the presentation at https://www.ehpa.org/fileadmin/red/09._Events/2019_Events/Market_and_Statistic_Webinar_2019/20190624_-_EHPA_Webinar_outlook_2019_-_Thomas_Nowak.pdf.

[4] For an admittedly extreme example, see the case of R (on the application of Farmiloe) v. Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and another [2019]. The claimant spent more than £240,000 on a renewable heat installation, in anticipation of receiving quarterly RHI payments of more than £8,000. However, he was at risk of receiving payments worth only about 13% of the original estimate because of changes to the scheme and its technical methodology.

[5] Please see Changes to the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) schemes for more information.

[6] Frank Gordon, head of policy at the REA (see his comments in the final paragraph of this article).]

Subscribe and stay updated

Receive our latest blog posts by email.