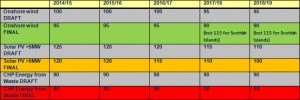

Only a few weeks ago, DECC announced the “final” strike prices that were to apply to contracts for difference (CfDs) for the various eligible renewable technologies under Electricity Market Reform (EMR) (see our earlier post on this). But things move fast in the world of EMR. On 16 January 2014, DECC announced that for those technologies considered “established”, there would be no guarantee of securing strike prices at the level of the figures fixed in December 2013.

The group of “established” technologies for these purposes consists of onshore wind (>5MW), solar PV (>5MW), energy from waste with CHP, hydroelectric (>5MW and <50MW), landfill gas and sewage gas. For these technologies, it is proposed that strike prices will be set by a process of competitive bidding for which the December figures will function as a cap. For the “less established” technologies (offshore wind, wave, tidal stream, advanced conversion technologies, anaerobic digestion, dedicated biomass with CHP and geothermal) the December strike prices will apply. A decision has yet to be made about strike prices for biomass conversion and Scottish islands projects.

Moreover, all technologies will have to apply for their CfDs through allocation rounds – i.e. at specified times, rather than whenever it is most convenient for them to do so. There will be no initial period of “First Come, First Served” allocation of CfDs. The draft CfD allocation framework, originally scheduled for publication in January 2014, will not now be published until March 2014.

The DECC announcement is cast as a consultation, but the key points look fairly firm. Although the document lists a number of factors that have been taken into consideration, it is clear that the European Commission’s draft state aid guidelines have played a big part in DECC’s thinking (see our earlier post on the draft guidelines). The draft guidelines place a heavy emphasis on the desirability of competition for subsidies to renewable generators.

There can be no doubt that the change of approach on strike prices ought to improve the chances of gaining state aid clearance from the Commission for the CfD regime. But what will be the practical and wider impacts of more projects having to compete on strike prices sooner?

How “technology-specific” will each auction be? How frequently will auctions take place? Some questions will have to wait for an answer until we have seen the allocation framework. For some time now, it has been clear that the allocation framework will be a hugely important document. Assuming that DECC sticks to its overall timetable, there will not be very much time to consult on the first allocation framework before the package of EMR secondary legislation that requires Parliamentary approval is laid before Parliament.

In the meantime, it is a fair bet that some projects which might have applied for a CfD will now opt for the more predictable support mechanism provided by the Renewables Obligation (RO) instead (as they will be able to do until 2017). Many of these projects are not large and the process of competing on strike price can only add to the costs of a CfD application. But if more opt for the RO from the outset, how will that affect the budget available for CfDs under the Levy Control Framework? And what will be the implications for any state aid analysis of the RO if projects that fail to win CfDs in the auction process can go on and claim what turns out to be a higher level of support under the RO?

Subscribe and stay updated

Receive our latest blog posts by email.