This is the fourth in a series of posts on the low carbon hydrogen policy documents published by the UK Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) on 17 August 2021, and the second of two posts on the forms of financial support proposed by BEIS for low carbon hydrogen projects. The three previous posts can be found here, here and here.

Mitigating volume risk in the hydrogen business model

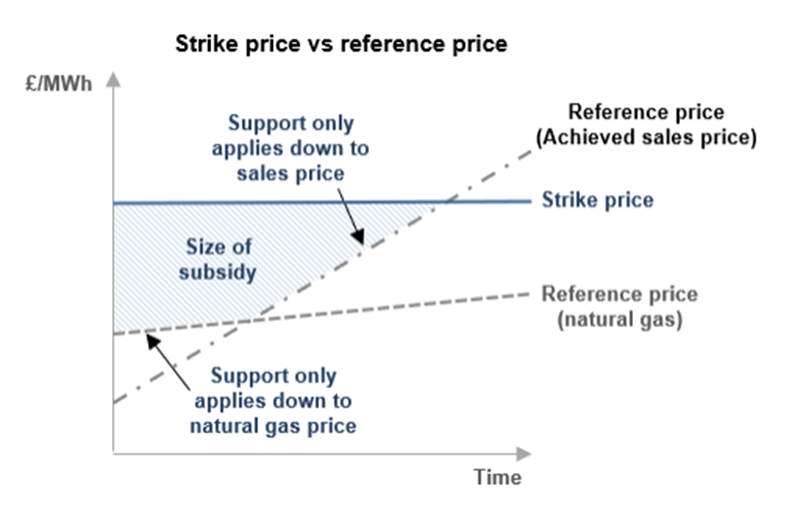

In the previous post, we explained how BEIS’s proposed “business model” (i.e. revenue support scheme) for low carbon hydrogen would mitigate the price risk facing producers. It may not feel like it to readers of the Hydrogen Business Model (BM) Consultation, but dealing with price risk is the easy bit of the business model. The real existential difficulty faced by early low carbon hydrogen projects is volume risk: what happens not when you cannot get a high enough price for the hydrogen you have produced, but when you cannot find a buyer at all? While there are things that can be done to mitigate volume risk outside the hydrogen business model (like facilitating the blending of hydrogen in the grid), these options may not be available to the first projects.

So, what are BEIS’s options for mitigating volume risk within the business model?

- Payments based purely on availability to produce would cost money without necessarily resulting in decarbonisation. They are no good for methane reformation technologies (which cannot ramp up quickly). Like capacity mechanisms in the electricity sector, they could turn out to be a drug on which the market gets hooked (with some insight, BEIS doubts its ability to refuse to NOAK projects what it would have conceded to FOAK projects in this regard).

- Government could purchase part of the producer’s output at a price that allows it to cover fixed costs, maintenance, debt servicing and a “minimum economic return” (MER) on equity. Government would be able to “take or pay” (or sell, store, flare or vent the hydrogen). This is highly interventionist, may distort the market and is less suitable for intermittent projects.

- Government could act as a buyer of last resort for volumes with no end user buyer. Rather than purchasing a set volume in each period, it would step in on a contingent basis and purchase the first volumes that cannot otherwise be sold. In any given period, this might be nothing, a bit, or a lot (subject to a cap). The price would have to be attractive enough to cover the MER, but unattractive enough to discourage reliance. The “backstop Power Purchase Agreement” for renewable electricity generators with CfDs who are unable to find commercial offtakers (included in the CfD as a confidence-building measure) is a partial model here. This approach would weaken incentives for producers to seek market demand; may undermine market formation; and would be hard for HMG to budget for.

- A government obligation to purchase could be triggered when the hydrogen offtake volume falls below the level at which the producer cannot cover MER. It would thus apply to lower volumes than the previous option, but with higher levels of support per unit. The producer would be obliged to sell the “government share” first: if it cannot achieve the guaranteed price, the government would make up the difference. If it achieves a higher price than the guaranteed price, it would pay the difference to the government. This shares some of the problems of the previous option.

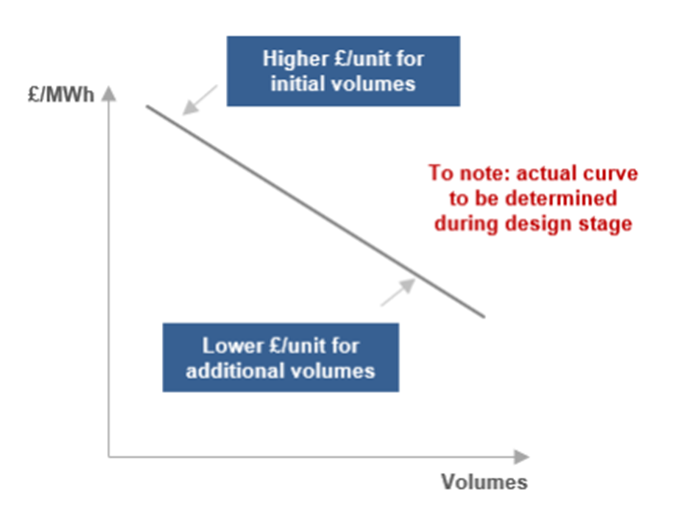

- Finally, there is the sliding scale. This would allow the producer to earn higher unit prices where offtake volumes are low, with support declining per unit as they rise. It would incentivise the producer to find offtakers because it would not be paid for not producing. It would avoid the risks and complexity of government buying “in the market”. More negatively, it delivers no support if volumes fall to zero; it is likely to become a permanent feature of the market; and it would be necessary to avoid perverse incentives around plant sizing.

The sliding scale is BEIS’s current preference. It would be delivered through the mechanism of a variable premium set by the relationship between a reference price and strike price, outlined in the previous post, but the BM Consultation does not say exactly how the sliding scale would be overlaid on this.

Other aspects of the hydrogen business model contract

Important as price and volume risk are, other things matter in a support contract too.

The BM Consultation lists a number of factors relevant to fixing the duration of support contracts and notes the precedent of 15 years for renewables CfDs, but offers no firm proposal.

It raises the pertinent question of “volume scaling”. If a plant increases its capacity, should it get business model support for the increase in capacity? The options are “yes” (potentially expensive and poor VfM); “no” (could limit market development); and “up to a pre-agreed maximum at a reduced level”.

BEIS indicates a robust line on construction overrun risks, technology/decommissioning costs; and input fuel supply disruption (all would be for the producer to manage), but it is looking at ways to help producers manage specification risk where the failure to meet specification is not their fault.

Contract allocation

BEIS’s discussions on how to address price and volume risk are at pains to be even-handed, pointing out where one option or another may not work well for a certain type of project. That does not mean that all kinds of hydrogen project will have an equal chance of obtaining business model support.

The renewables CfD regime has allocated funding largely through strike price-based auctions since 2015, but it was first road-tested with a less transparent allocation process that awarded eight (fairly generous) early CfDs in 2014. For the hydrogen business model, BEIS sees auctions as the way forward in the medium term (including different “pots” for certain kinds of project, as with renewables CfDs) but, in the first instance, it envisages that contracts will be awarded through negotiations. For projects embedded in CCUS clusters, this would be part of the ongoing CCUS cluster competitions; a similar process for non-CCUS enabled projects will be announced in due course.

In either case, the key words in the BM Consultation are: “We expect to set out specific eligibility criteria each time we open an opportunity to allocate BM support”. In other words, there will be further hoops for projects to jump through. These may not detract from the technological neutrality of the business model, but they may well be designed to focus early support on those projects that appear, for example, to be least exposed to volume risk.

NZHF and projects outside the hydrogen business model

We have not said much so far about the Net Zero Hydrogen Fund (NZHF) Consultation. Compared with the BM Consultation, it describes a rather simpler policy at shorter length and in less detail. The key points are as follows.

- Although the hydrogen business model and Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation (RTFO) will provide revenue support for low carbon hydrogen projects, BEIS still sees a role for upfront capital cost support to reduce the quantum of costs and risks for such projects. There is a clear concern that projects will need a “bridge” between the innovation funding that may have supported their earliest stages and commercial financeability.

- The NZHF aims to stimulate new low carbon hydrogen production, demonstrate commercial use of the technologies and build a pipeline of projects towards the 5GW 2030 target.

- It will be based on capital grants. Equity participation and capital guarantees are ruled out as unduly complex; government loans “may not go far enough in removing risks and barriers”.

- Funding will, in principle, be available both to projects that do and to those that do not require revenue support (e.g. via the hydrogen business model) – although the expectation, or hope, would be that capital co-funding for projects should reduce the revenue support they require.

- Projects supported outside the hydrogen business model are likely to be “smaller, often electrolytic” projects supplying transport sector end users and benefiting both from the relatively high cost of the counterfactual fuel (diesel) and RTFO revenue support.

- The focus would be on capex co-funding (“offering a percentage of the initial project cost estimate, including contingency”) and on supporting development expenditure at the feasibility, pre-FEED, FEED, and post-FEED/pre-FID stages.

- Projects would be expected to “demonstrate [their] socio-economic and industrial benefits”. They must be UK-based, with core technology at Technology Readiness Level 7 or higher.

- If applying for capex funding, they must “prove they have an agreement in principle with an offtaker for some or all of their production volumes”. For devex funding, there is a vaguer requirement to “demonstrate demand for the hydrogen”.

- Private sector financial backing must be demonstrated, and an ability to take FID by 2025. RTFO approval must be obtained where RTFO funding is relied upon.

- A series of periodic competitions for funds is scheduled to start in early 2022.

Where will the money (and the legal powers) come from?

On the question of how payments to producers under business model contracts will be funded, the BM Consultation offers two thoughts. “A Call for Evidence on energy consumer funding, affordability and fairness is expected to be published soon.” “Further details of the revenue mechanism [to fund the business model] will be provided later this year.” The recent increase in domestic energy bills as a result of a rise in gas prices has come at an awkward time for new energy funding schemes, given the UK’s historic reliance on consumer levies to fund new low carbon projects (a trend of which the latest representative is the draft Green Gas Support Scheme legislation for biomethane). Watch this space.

Clearly, any levy or other funding mechanism for the hydrogen business model similar to those that have underpinned renewable electricity subsidies would require legislation. More generally, it is hard to imagine how the whole scheme of the business model would or could be implemented without new legislation, probably including primary legislation, to support it.

The same is not true of the NZHF. It is assumed that government already has the money for this, and that it can be disbursed contractually, relying on existing industry-funding powers.

However, both the NZHF and hydrogen business model will need to comply with applicable subsidy control rules (although the NZHF Consultation highlights this issue more than the BM Consultation). At present, the UK regime is in transition from being governed by EU state aid rules (which, however, still apply in respect of Northern Ireland) to a new domestic regime that is still being legislated for.

The BM Consultation notes that BEIS is keen to explore the possibilities of projects “revenue stacking”, with different elements of public financial support. The concept of “revenue stacking” has been central to the development of many new electricity generation and storage projects in recent years. However, where the layers in the stack may be classified as subsidies (which has not been the case with, for example, revenues from grid ancillary services), care needs to be taken to avoid “overcompensation” and therefore breach of the subsidy rules.

What next?

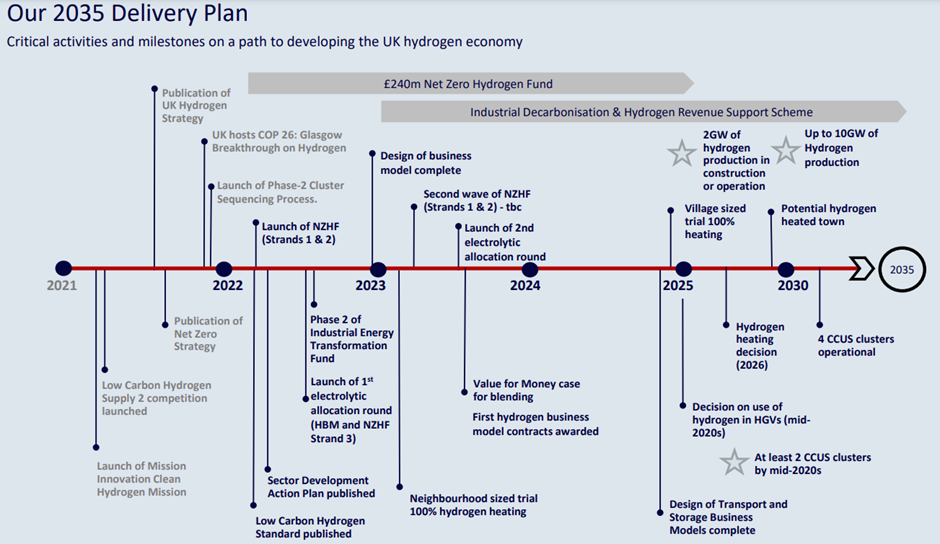

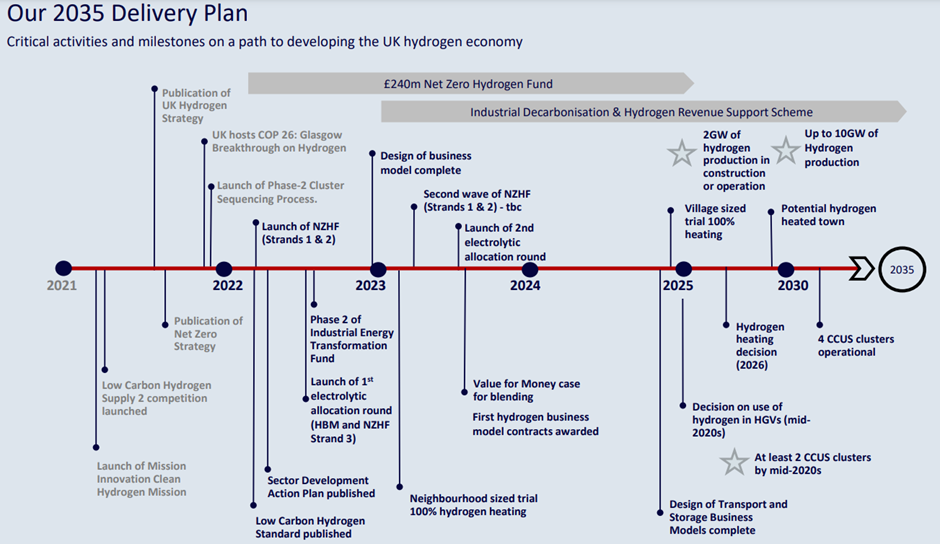

With heads of terms for the business model due to be published, alongside a response to the BM Consultation, in Q1 2022, and the first contracts to be signed in 2023, BEIS has no time to lose in putting flesh on the bones of the business model as outlined here. And, as noted above, the launch of the NZHF is scheduled for early 2022, indicating rapid movement on that front too.

In the meantime, the background will not stand still. In particular, although the BM Consultation carefully tries to examine the various options for designing the business model in isolation from other policy developments, the Hydrogen Strategy promises an announcement on the UK’s “aspirations to continue to lead the world on carbon pricing” in the run-up to COP26 in November.

Even though it does not see carbon pricing as sufficient in itself to stimulate low carbon hydrogen projects, there are plenty of things that the government could do to help mitigate both price and volume risk by extending the reach or increasing the level of UK carbon pricing. For example, it could tweak the climate change levy and its many exemptions, or mirror the EU’s proposed extension of GHG emissions trading to new sectors (heat and transport) or its proposed adoption of a border carbon adjustment – all steps which could have benefits (and costs) beyond the hydrogen sector.

These are exciting (albeit, in the short term, rather uncertain) times for UK hydrogen projects. Those hoping to benefit from the support proposed in the BM Consultation and NZHF Consultation have until 25 October 2021 to respond to BEIS with their views. If you would like to discuss how the proposals may affect your project or how to put your case most effectively to BEIS, please get in touch.

Subscribe and stay updated

Receive our latest blog posts by email.