The UK and Europe have set highly ambitious targets for developing offshore wind (OSW) over the coming decade, yet the industry is currently suffering supply chain challenges which threaten new projects. Measures that could mitigate these challenges include (i) new criteria for consenting/allocating support to OSW projects which give more weight to supply chain factors rather than simply awarding on price (ii) deeper collaboration/standardisation within the industry. This article examines the competition, subsidies and WTO law issues which these solutions may give rise to.

Executive summary

The decline in wind turbine orders last year, coupled with the rapid expansion in global demand for OSW projects, means that new policy solutions will be required to ensure that OSW projects are incentivised to proceed, and can do so profitably. Competition and subsidies law, and trade law, can limit the levers which are available for governments supporting individual projects and the industry more widely.

This article concludes the following:

- The use of non-price criteria (such as environmental and supply chain contribution) to allocate support to OSW projects could support domestic supply chains and allow projects of strategic importance to be selected and at acceptable prices. Subsidies and EU state aid law have traditionally favoured competition based purely on price, but this picture looks set to change. The recently published EU proposal for a Net Zero Industry Act[1] imposes specific requirements to take sustainability and resilience into account in renewables auctions.

- Trade law complaints are always a risk when a WTO member takes active steps to subsidise and support local supply chains. In the geo-political context of the US and EU taking similar measures to support low carbon technologies, it would appear more likely that complaints about protectionist behaviour are resolved by political rather than legal means.

- Competition law restrictions must be taken into account when industry collaborates as part of joint projects, or to improve processes. Risks can be mitigated based on careful structuring of projects.

Background: offshore wind targets and industry obstacles

As part of the drive towards net zero, a significant growth in offshore wind capacity is envisaged over the coming decade.

The UK government has ambitious offshore wind energy targets, aiming to secure 50GW by 2030[2].

The EU has a target (from the REPowerEU plan) of 480GW of wind capacity by 2030 (up from about 190GW today).

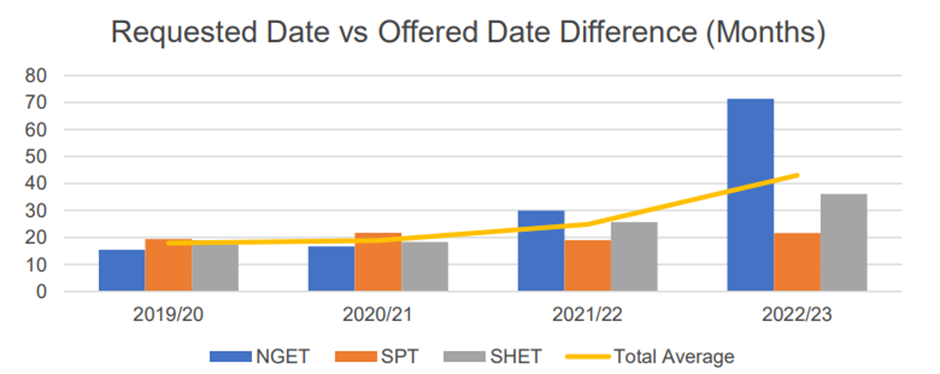

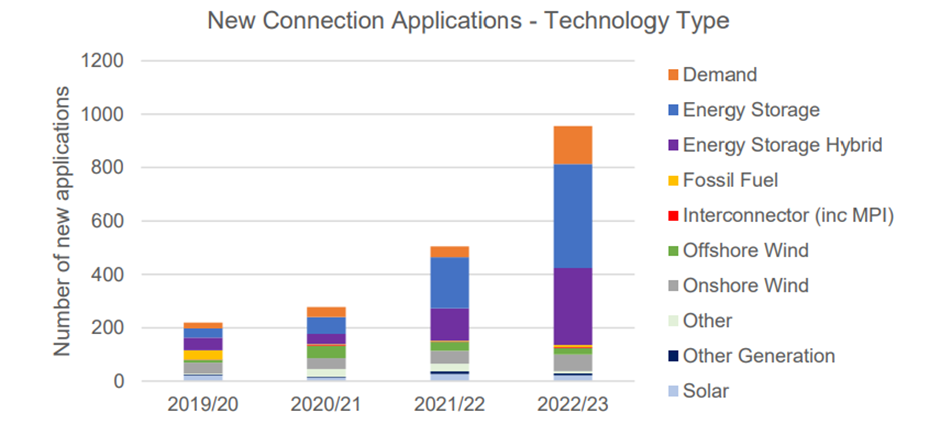

Offshore wind developers have raised several significant obstacles in this regard. One relates to inability of new projects to connect to the grid. In addition, there are significant supply chain challenges, as global markets grapple with post-Covid recovery which has been exacerbated by geo-political events.

The first key supply chain challenge is the fact that soaring gas prices caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has driven up the cost of industrial production of the materials, such as steel and copper, and components required to build wind turbines and the associated infrastructure. Therefore, costs for developers have sharply increased as suppliers have pushed up prices to deal with the increased cost of making turbines. Consequently, it is increasingly difficult for companies in the supply chain to predict where prices will go.

Furthermore, the industry is facing supply chain delays, started by the Covid-19 pandemic and exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. This has led to increased transportation and logistics costs with companies now at risk of having to pay “liquidated damages” to customers, or compensation payments due to project delays.

Another issue is the unavailability of equipment and vessels. The surge in uptake of offshore wind in the UK and globally has led to increased demand for specialised vessels, which can cause bottleneck delays for offshore wind installations. This is exacerbated by the trend towards larger turbines, as the development of technology and turbine size is exceeding the manufacturing pace of turbine installation vessels.

In the UK, it is reported that several offshore wind developers, which were successful in the most recent auction round for projects due to start generating capacity in 2024 have had to delay due to cost pressures, and are seeking additional subsidies or tax breaks from government[3].

Current relevance of auction processes

In the UK, a developer would typically enter two auction processes as part of developing an offshore wind project. The first is the seabed leasing managed by the Crown Estate or Crown Estate Scotland, which grants the developer options for access to the seabed, with developers historically based on who offers the highest payment for the option.

The second is the Contract for Difference (CfD) auction – a revenue stabilisation mechanism whereby projects compete for contracts which guarantee a market premium per unit of electricity generated through payment of a “strike price” when this is higher than a market reference price for approximately the first 15 years of the project. Projects compete for CfDs due to the revenue certainty they provide which in turn lowers finance costs, with successful projects bidding to bring the strike price down.

Traditionally, the benefit of auctions has tended to be lower prices for consumers (or more revenue for government). Where projects compete on price, this means those projects that are able to minimise their supply chain costs will be more competitive. One downside, however, is that opting for the lowest cost supply chain inputs (which are more likely to be imported) means that it is harder to build a domestic industry with necessary expertise. Another downside is that where projects are in tight competition to obtain CfD support (which tends to happen relatively late in the consenting process) there is less incentive to collaborate – even where such collaboration could improve innovation and ultimately lead to cheaper inputs.

Potential solutions: auction design – non-price criteria

One solution to support supply chains would be to take into account selection criteria other than price in awarding support contracts. Suggestions for such criteria are necessarily generic in nature and would need to be tailored to suit the specific competitive context, and the contract that is being awarded. Options include:

Supporting supply chain stability and resilience

This criterion acknowledges and rewards a project’s contribution to the enhancement of domestic/regional supply chains. This tends to be an important policy aim for host governments, but it is difficult to achieve in a highly cost-competitive environment. Offshore wind in the UK has a number of industry initiatives[4] (often backed by government) to strengthen the supply chain. As noted below, it can be difficult to reconcile supply chain commitments with trade law and subsidies obligations.

System integration and innovation

Systems integration and innovation involves combining offshore wind projects with other technologies and capabilities that help economies decarbonise and produce greater value from the offshore wind project. One example could be pairing offshore wind with electrolysers to produce hydrogen, making offshore wind farm production hubs for green hydrogen. This will be most relevant in markets where the share of renewable resources is high. Another example is the use of multi-purpose interconnectors which would allow clusters of offshore wind farms to plug into an interconnector, enabling offshore wind and interconnection to work together more cost-effectively as a combined asset.

Environmental factors

These can include a lower environmental impact of the project, enhanced coexistence with other marine activities and the optimised use of the sea. More widely, sustainability may also be taken into account in reducing the lifecycle emissions of offshore wind projects, and ensuring the recyclability of materials.

Regulatory structures to support the policy aims underlying these criteria are not new. For example:

- As part of the process of qualification to participate in CfD auctions, offshore wind developers are required in certain circumstances to submit supply chain plans for approval by government. Failure to comply with those plans can lead to payments being withheld once a CfD is in operation. Whilst the actual auction is based on price, this requirement for a supply chain plan introduces local content considerations. As discussed below, the EU initiated a challenge before the WTO in relation to the UK’s offshore wind supply chain plan requirements.

- Similar supply chain local content expectations are contained in the requirement to deliver a Supply Chain Development Statement under the recent Scotwind seabed leasing round in Scotland, with the threshold of supply chain commitments that applicants must meet increasing from 10% to 25% (underpinned by an obligation under the Scottish Crown Estate Act 2019 for Crown Estate Scotland to deliver wider benefits such as economic development and environmental well-being). The Crown Estate’s floating offshore wind seabed leasing auction in the Celtic Sea will also require participants to outline a plan for supply chain contribution.

- The UK is considering adding further non-price criteria as flagged in its consultation document on policy considerations for future rounds of the CfD scheme, although the consultation states that this would have to be balanced against higher costs to consumers.

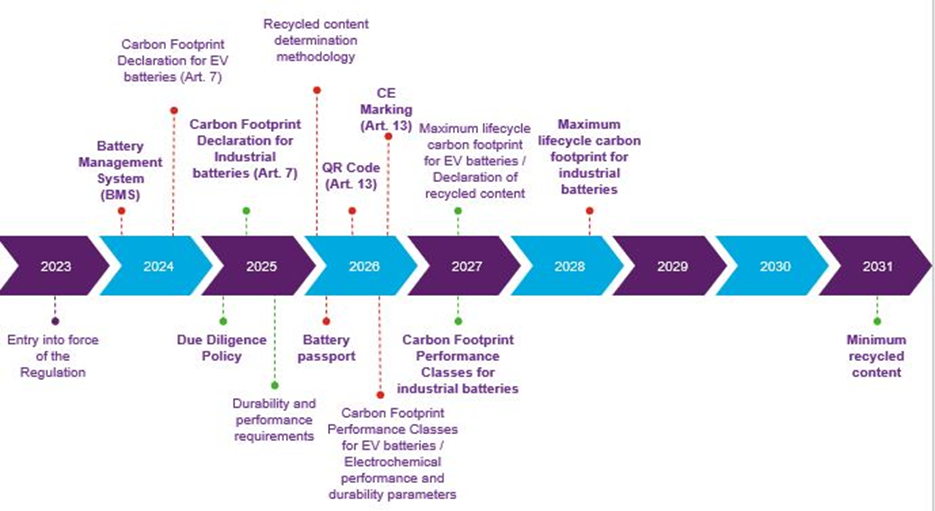

- The European Commission adopted new environmental state aid guidelines in January 2022 which update the basis on which the European Commission will approve state aid for projects that contribute to decarbonisation. The guideline states that when allocating aid in a competitive bidding process, it may be appropriate to include (non-price) selection criteria up to 30% of the weighting. This is a departure from the existing approach that the amount of state aid granted must be at the lowest level possible (i.e. the minimum intervention to achieve the outcome). In addition, the Commission is currently consulting EU member states on changes to the “state aid temporary crisis framework” which include amendments to allow support for investments in the production of strategic equipment necessary for the net-zero transition, with wind turbines specifically included in the list of such strategic equipment.

- Further, the EU’s proposal for a Net Zero Industry Reduction Act (Article 20) includes a specific requirement (subject to the Union’s international commitments and state aid law) for member state authorities to assess the sustainability and resilience contributions of projects, with a target weight of between 15% and 30%, when designing the criteria used for ranking bids in renewables auctions.

- Further afield, the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) includes new and revised tax incentives for clean energy projects, significantly modifying the federal tax credits available for renewable energy projects. The IRA has extended certain tax credits to wind projects, with credits increasing where projects satisfy requirements regarding domestic content, wage and apprenticeship rules. The EU trade commissioner has complained informally about the discriminatory treatment this entails for foreign suppliers.

This demonstrates a wider trend of host governments taking measures to ensure that financial support for renewables projects also results in domestic benefits in terms of supply chains, industrial capability and jobs/skills.

Non-price criteria: trade law and subsidies considerations

International trade law

Measures which give preference to domestic industries risk falling foul of WTO law requirements.

Under the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures, two categories of subsidies are prohibited. These are subsidies that are either contingent on export performance (known as export subsidies) or contingent on the use of domestic goods over imported goods (known as local content subsidies). A wider range of subsidies is actionable: not necessarily prohibited, but capable of challenge if they have had, or will have, an adverse effect upon another WTO member. Examples would include a government subsidy for a new project, which would lead to unfair price suppression in the type of products it produced and displace the exports of another WTO member in a market.

Whilst subsidy challenges are some of the most common WTO GATT cases, they are always heavily fact-specific. The risk of challenge is greatest when there is an obvious and severe negative impact on another country’s industry. The IRA has already sparked talk of subsidy challenges. In a November 2022 speech, European commissioner for trade Valdis Dombrovskis referred to the EU’s “serious concerns” about US green subsidies discriminating against EU automotive, renewables, battery and energy-intensive industries and “potential new disputes”. Equally, the EU’s latest “Net Zero Industry Act” may raise concerns of protectionism and preferring EU-based content. The EU and US have established a joint high-level task force to address the issues.

The EU requested WTO consultations to the UK’s green energy subsidy scheme in March 2022, on the basis that criteria used by the UK government in awarding subsidies for offshore wind energy projects favoured UK over imported content. The EU alleged that this violated the WTO’s “core tenet” that imports must be able to compete on an equal footing with domestic products and harmed EU suppliers. The dispute was resolved in July 2022, with clarification from the UK that CfD beneficiaries did not need to achieve any particular level of UK content to receive payments.

It is possible to rely on the security exception under GATT as a defence to any potential challenge. Under Article XXI, a WTO member shall not be required to furnish any information, the disclosure of which it considers to be contrary to its essential security interests. Blocking the disclosure of information about subsidies could effectively mean that any challenge brought by another WTO member could face significant barriers in succeeding due to lack of information on the subject of the challenge.

UK subsidy control regime

The UK regime is still very new and, importantly, operates differently to the EU state aid system. The obvious benefit is its greater flexibility and speed. So long as the relevant public authority is satisfied that the principles set out in the Subsidy Control Act 2022 are met, it can generally award the subsidy unless it, and related subsidies over a three-year period, are above £10 million.

The main risk is of challenge by third parties (most likely competitors) in specialist proceedings before the Competition Appeal Tribunal (details of all awards above £100,000 must be published on a subsidy database). However, there are strict time limits and it is not yet clear whether there will be an appetite to incur the costs of going to court. In addition, if subsidy is given under a scheme, it is the scheme that would be open to challenge. Once the time limit expires, the subsequent individual awards under the scheme would not be capable of challenge (so long as they meet the scheme’s criteria).

Subsidies of more than £10 million (or schemes set up to award individual subsidies above that amount) must be delayed until the CMA’s State Aid Unit issues a non-binding opinion on the public authority’s assessment of compliance with the requirements of the Act and a short cooling-off period has expired. This advice could lead public authorities to reconsider the design of an auction, for example, but only if serious issues are identified with the initial assessment of compliance. The first subsidy scheme reviewed by the CMA’s State Aid Unit was the Contracts for Difference (CfD) for Renewables scheme. In a report published on 28 February 2023, the CMA did not find any serious issues with the assessment carried out in relation to the fifth CfD allocation round (AR5), but it did give some advice as to how the assessment could have been strengthened in certain areas, which will be useful for the future assessment of subsidy schemes.

Although there is no specific guidance dealing with offshore wind, the new regime in the UK means that auctions designed on the basis of price and non-price factors can, in principle, be compliant with the Act, provided there is sufficient evidence that the subsidy/subsidy scheme is in line with the relevant principles (and does not involve prohibited types of subsidy, such as those that are contingent on the use of “local content”, as mentioned above). The principles are not prescriptive about how a competitive process should work, so long as the subsidy is proportionate to the specific policy objective.

EU state aid

As noted above, the guidelines appear to recognise that flexibility is needed, though are now relevant only to the extent that subsidies are awarded to UK recipients by EU member states (or if the Northern Ireland Protocol is engaged, meaning that EU state aid law continues to apply).

Potential solutions: developer collaboration and competition law considerations

Closer industry collaboration can be an important part of the solution in making offshore wind supply chains more sustainable and profitable. This could manifest itself in a number of ways, including standardising design features to allow for economies of scale in construction, and reducing maintenance and equipment costs. In terms of legal structures, the following are of particular interest:

- Joint projects: These can include collaboration in developing new projects or in relation to service industries – for example, combining project management and engineering expertise to provide services such as subsea surveys, yard services, maintenance and repair etc. This could be relevant to ports that would otherwise be competing to secure offshore wind services such as locations for manufacturing components of OSW projects or assembly and marshalling of components or O&M services.

- Knowledge sharing: This can include informal or more structured ways of sharing know-how and resources, and of advocating for regulatory changes. Examples include the Scottish Offshore Wind Energy Council (SOWEC) Offshore Wind Collaborative Framework Development where (amongst other outputs) parties share strategic information, explore contractual and procurement mechanisms, and ensure sector-wide communication.

- Standardisation of legal contracts: For example, FIDIC contracts are commonly used for offshore wind construction projects but with significant amendments. There may be further scope to standardise.

Competition law is often regarded as a barrier to effective industry collaboration, with the risks being too great (financially and reputationally) for anything other than a cautious approach. In the context of offshore wind, there are certainly important risks to navigate, but that does not mean that collaboration cannot be achieved and should not be explored. Competition authorities recognise that a joined-up approach can produce benefits for competition, provided certain criteria are met, and there are tentative signs that environmental benefits might also be taken into account in this assessment.

Certain types of collaboration may not engage competition law. This might be the case, for example, where companies bid jointly for a licence and would not have been able to do so independently (perhaps because they offer complementary services/products or it would be too costly/complex to bid individually).

If prospective JV partners could bid individually, or the collaboration is of a different nature between competitors, the parties will need to weigh up the restrictive effects of the arrangement on competition against the benefits for consumers, but there may be a way to collaborate in a compliant manner.

The odds have recently improved in this respect. The UK competition authority has recently announced that wider environmental benefits to society can be taken into account in this assessment, provided the agreement is aimed at making a substantial and demonstrable contribution to tackling climate change (an argument likely to be available, at least in principle, to many types of collaboration relating to offshore wind). Not only that, but the CMA has indicated that it will operate an “open door” policy and will provide informal advice to businesses about their proposed arrangements, providing comfort that the current self-assessment approach did not. Parties will, however, need to be able to demonstrate and quantify the claimed benefits.

There are examples of successful industry-wide collaboration in the UK, which show it can be done. The oil industry regularly participates in joint ventures to bid for licences. That industry was also encouraged to collaborate to maximise economic recovery (MER) in the North Sea. Whilst the UK competition authority expressed concerns, cautioning against arrangements which would lead to collusion and the exchange of competitively sensitive information, guidance was subsequently produced by the Oil and Gas Authority on how these issues could be managed and the benefits unlocked.

[1] https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-03/COM_2023_161_1_EN_ACT_part1_v9.pdf

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/british-energy-security-strategy/british-energy-security-strategy

[3] https://www.ft.com/content/80dee308-a564-4ee4-b1f2-ab7dbed643cd?shareType=nongift

[4] For example, see Catapult here

Subscribe and stay updated

Receive our latest blog posts by email.