As noted in our recent post on Shared Ownership, the UK Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC) has published its Community Energy Strategy (Strategy) which anticipates that by 2015, it will be normal for new renewable energy developments to offer project stakes to local communities (and which could be enforced by an enabling power in the draft Infrastructure Bill 2014). At a recent renewable energy industry event, it was asked why shale developers are not similarly targeted by the Strategy to offer stakes to local communities?

Analogy to a new tax

In short, because it would likely be argued to be unfair. Shale developers have already paid and committed to fulfil minimum work obligations onshore under a petroleum, exploration and development licence, in order to have the right to explore for and later extract hydrocarbons from the sub-surface (and off the Crown). Any later requirement to give a royalty or equity interest to a local community, could be regarded as being analogous perhaps to an unexpected new tax. In addition, having to obtain DECC consent or adding say a community interest company (CIC) vehicle to a hydrocarbon licence, could be administratively cumbersome.

Misalignment of local opposition

That said, renewable developers may argue that buying or leasing surface land rights for renewable energy generation, and later having to give a stake to a local community, is little different philosophically. However, the current Strategy proposal is perhaps designed to address the apparent misalignment between national poll results (which are reported to suggest a majority are in favour of renewable energy); and local communities (who often resist wind and solar developments in their own localities). Such opposition is often then said to be reflected in local authority planning application refusals, which in turn reduces renewable energy development and impacts national carbon targets.

Reduced justification for compensation

By comparison, opposition to shale developments, is perhaps expected to be less driven by local planning or land-use opposition, as opposed to broader ideological and environmental concerns, which may not be as effectively addressed with active community participation – few well-heads will have the “wow factor” of a windmill. In addition, once DECC’s current consultation on granting horizontal drilling access rights (to ease shale and geothermal developments) runs its course (see our recent post Compulsory access rights “in the national interest”), then developers will possibly have less need for community alignment on specifically land-use environmental concerns. Indeed, the relative thickness of exploitable UK shale resources means that relatively few well-pad sites on the surface could be used to access large areas of sub-surface resource horizontally, causing little environmental impact (truck movements apart). This may reduce any justification for giving local communities a substantive share of the profits.

Conclusion: proactivity in hindsight

It is also important to note that the nascent shale industry, to the extent represented by the recently invigorated UK Onshore Operator’s Group (UKOOG), has perhaps already drawn some of the sting of potential community engagement regulation, by pro-actively suggesting well-pad and production payments (albeit modest in amount) for local communities. Whilst the renewables industry is more mature, numerous and with diverse interests, it may be noted that a sophisticated regulator is rarely motivated to act, except where market failure is perceived. Therefore, if the shale industry were to fail to implement the recommendations volunteered by the UKOOG, DECC may be tempted to re-assess the absence of unconventional developments from the Strategy and Infrastructure Bill’s proposals for community participation. In hindsight, now that DECC has seen a need to prompt the renewable energy industry into volunteering community participation, it appears less likely that community payments divorced from equity stakes or project profitability alone, will meet the regulator’s perception of community needs.

For further analysis on the potential application of UK and other international examples for tailoring legislation, farm-in and joint operating agreements in developing unconventional basins, please see our Shale Guide, recently presented and discussed over two days in Washington DC at a World Bank and OGEL symposium, aggregating the learning of representatives covering 18 countries.

Subscribe and stay updated

Receive our latest blog posts by email.

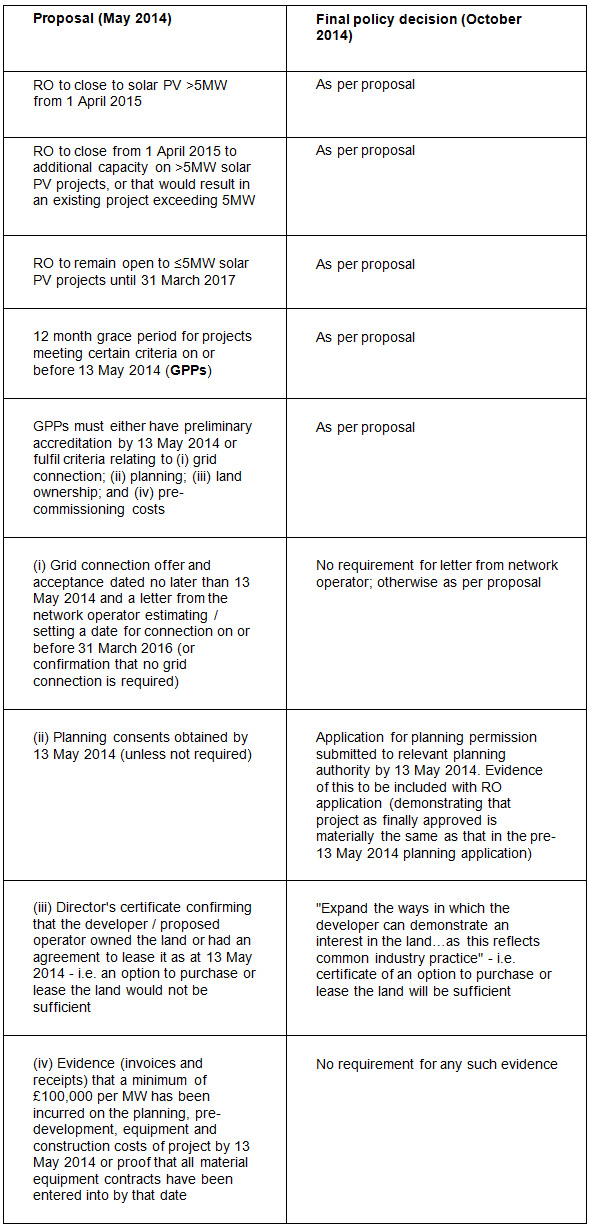

HSE and DECC have been busy drafting and amending legislation to transpose the

HSE and DECC have been busy drafting and amending legislation to transpose the